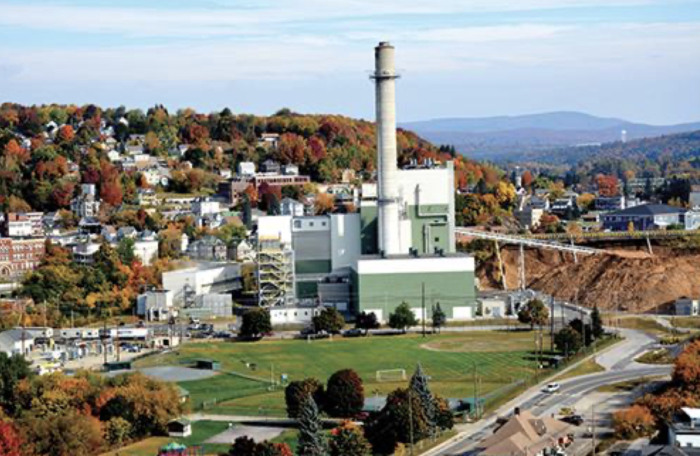

The Burgess Biopower ratepayer money pit

If the Burgess Biopower plant in Berlin closes, New Hampshire electricity customers will save money. The state’s shrinking timber industry (and the City of Berlin) will lose money.

The Legislature is again faced with the prospect of choosing sides. And again a proposed bill would side with the timber industry, not ratepayers.

It’s a long and complicated story. Let us explain. No, that is too much. Let us sum up.

The plant burns wood pulp, largely but not entirely from New Hampshire. Eversource buys power from the plant at above-market rates mandated by the state.

These higher payments are not to support “green energy.” The plant is just a conduit for funneling money to the timber industry. It exists to create a market for New Hampshire wood pulp. It’s a jobs program, not an environmental program.

But it’s a jobs program funded by a mandatory rate increase on Eversource customers. That’s highly regressive and economically harmful. Low-income families pay more for electricity, as do employers.

To reassure the public that this wealth transfer scheme wouldn’t get too out of hand, the state capped total above-market customer payments to the plant at $100 million. Whenever the customer overpayments pass the $100 million mark, the plant has to reduce its prices so that ratepayers recover the difference within the next 12 months.

Thanks to falling natural gas prices, the cap was hit several years ago. So the Legislature intervened again and suspended the cap for three years. That suspension ends this November, at which point the plant will have to lower its rates to let customers recoup the last three years’ worth of overpayments.

Uh oh.

Eversource estimates the three year total to be $58.8 million by the end of November. If the plant must repay that within 12 months, it will have to close, its officials have testified.

The state has a few options.

It could amend the agreement to let the plant repay the money over a longer period of time. This might not save the plant in the long run, but it could buy time (assuming the plant can afford to rebate the money at all).

It could directly subsidize the plant with payments from the General Fund.

It could let the plant close. That would save ratepayers an estimated $2.50 to $3 a month, according to the Department of Energy. Large customers (employers) would save much more.

Or it could pass a law to basically forgive the $58.8 million in customer overpayments. That’s what Burgess Biopower says Senate Bill 271 would do.

The bill might do more, though. It states that “any and all legislative relief provided to the Burgess BioPower plant shall be deemed to be reasonable, legitimate, and in the public interest….”

Any?

Through the end of 2021, Eversource customers have already paid more than $150 million in above-market rates for electricity generated by the Burgess Biopower plant. The plant cost a reported $275 million to build. But ratepayers don’t own 54% of a power plant. They just threw their money away. Well, the state threw it away on their behalf.

It’s likely that by the end of the 20-year contract, the overpayments will total more than the plant cost to build. And that doesn’t include the above-market payments for Renewable Energy Credits that are mandated by the agreement.

Burgess representatives say the plant supports 240 industry jobs. If we accept that number for argument’s sake, ratepayers have already spent more than $640,000 per “job saved,” with years left in the contract.

This is a huge transfer of wealth from Eversource customers to a few hundred people (at most) in an industry that is economically declining but politically well-connected.

Burgess Biopower officials say the plant won’t need any more handouts if the $58.8 million in overpayments is forgiven. But the contract that forces customers to pay above-market rates continues. That’s a handout.

The state’s scheme to subsidize the plant will continue to cost ratepayers more than $20 million a year through the life of the 20-year contract, according to the Department of Energy. The plant began operations in 2014.

And when all of these subsidies are done, what will the ratepayers have to show for it? Probably nothing. If these above-market payments were actually “investments,” they would have purchased shares in the plant’s parent company. Then, at least the ratepayers might have gotten something in return.