A recent New Hampshire Public Radio story about New Hampshire’s last remaining coal-fired power plant offers a great example of how left-wing activists enjoy an unwarranted ability to frame journalistic narratives, particularly on energy issues.

“New Hampshire’s coal-fired power plant, the last of its kind in New England not set to retire, will now remain online through at least 2025, despite calls from climate change activists for it to close,” NHPR reported.

To see how this framing elevates the activists’ position, just apply it to other stories involving non-leftist protesters. Imagine public radio stories written this way…

- “New Hampshire’s remaining abortion clinics remain open despite calls from anti-abortion activists for them to close.”

- “Democrats raise taxes despite calls from anti-tax activists for tax cuts.”

- Schools remain closed for in-person instruction despite calls from parents, pediatricians, and epidemiologists that they open.”

Activists on the political left are treated by the media as morally and factually correct by default. Their complaints, protests and demands are accepted as morally serious and intellectually rigorous without question.

Because of this, a handful of radical activists have their publicity stunts and press releases covered with tones of gravity and seriousness, as if their positions represent basic common sense, while the same courtesy is not given to businesses or non-leftist activists.

In this framing, the activists are treated as morally superior, or at least as representing the reasonable, generally accepted point of view.

But are they?

The real story regarding Merrimack Station’s continued existence is that New Hampshire’s last coal-fired power plant will remain available as a backup source of power for another two years to provide a hedge against the risk of blackouts during periods of peak demand — because coal has qualities essential for a backup fuel source. It is reliable, storable, cheap and available.

It’s reasonable to say that coal shouldn’t be needed in New England anymore. Cleaner alternatives could have replaced it as a source of backup power it by now.

But the availability of those alternatives has been restricted by the very activists who demand that Merrimack Station be closed immediately.

By fighting natural gas pipeline expansion proposals, environmentalist have ensured that higher-CO2 emitting coal- and oil- fired generators will continue to be needed to ensure reliability of New England’s electricity grid.

New England’s electricity market is only partially deregulated. The grid operator, ISO New England, is charged with ensuring that electricity is delivered 24/7, 365 days a year. The provision of that power is not left entirely to the market. The grid operator pays some power generators to keep generation facilities on standby in case their power is needed in an emergency.

That’s the case with the coal-fired Merrimack Station. It receives capacity payments to ensure its availability to run on (mostly) cold days when natural gas is being used to heat homes, limiting its availability to generators.

Because power is needed when all other generation is at or near max capacity and when fuel (whether that be natural gas, sun and/or wind) is restricted or unavailable power has to come from a source that can be “dispatched”—coal, oil or pumped storage (hydro) .

Nuclear Power is emissions free and is a highly reliable workhouse that operates at very high capacity factors. But nuclear plants have been expensive to build, in part because of regulations and court cases brought by activists. Environmental activists have successfully restricted the supply of nuclear power in New England by using activism and legal challenges to prevent the creation of new reactors and to get existing ones shut down.

Natural gas, which burns cleaner than coal, might be able to fill the gap on peak demand days. But as ISO New England has pointed out for years, supply and storage constraints make this risky.

Natural gas plants rely on just-in-time delivery of gas. As mentioned above, environmental activists have successfully blocked the pipelines, import terminals and storage facilities that would make natural gas a viable replacement for coal for emergency power. This shortage makes it too risky to rely solely on natural gas as a backup source during periods of peak winter demand.

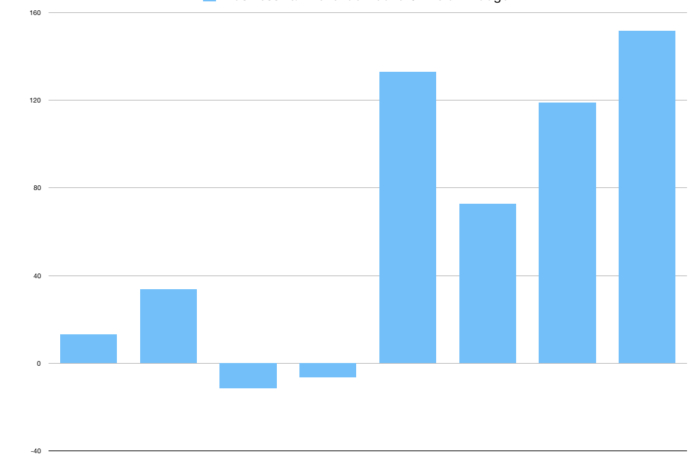

In general, natural gas is cheaper than coal as an everyday fuel source, thanks to fracking (which environmental activists also oppose). But on very cold winter days and in late summer heat, when natural gas is in high demand, prices rise, and coal becomes competitive on the market.

Wind and solar power operate approximately 30% and 15% of the time because they require favorable weather conditions which are often unpredictable. Without massive storage capacity, which is very expensive and not practicable for large-scale deployment, wind and solar aren’t capable of being dispatched to respond when the grid is stressed.

Coal can be stored on site in large quantities cheaply. With a shortage of other storable, reliable backup fuels, coal can be used in a pinch. That’s exactly how the Merrimack Station plant is being used.

The grid operator is charged with ensuring both reliability and market efficiency. That makes coal a go-to source of backup power for the few days a year in which natural gas supplies are being diverted from electricity generators to home heating. The grid operator essentially accepts higher carbon emissions for a few days a year for the purpose of ensuring that power is available.

That tradeoff is at the heart of the issue. The activists prioritize emissions over all else. They don’t accept the tradeoff. But their position is extremely risky and costly.

The power grid operator prioritizes reliability over emissions for good reason. It saves lives.

If New Englanders were asked whether they’d be willing to trade a few days’ a year worth of higher carbon emissions for a guarantee that they don’t run out of power on the coldest winter and hottest summer days, most would probably say yes without hesitation.

Radical environmental activists already have made clear that they don’t accept this tradeoff. They might not care that the tradeoff actually involves a higher risk of blackouts. But the grid operator does and is committed to hedging against that risk.

Given the alternatives, isn’t hedging against the risk of blackouts the more morally serious and responsible position?

That brings us back to the question at the beginning.

Do radical green activists really have the morally superior position here?

The answer is pretty clearly no.

It’s not an ideal tradeoff, but given the limited options available, keeping the state’s last coal plant open to ensure that people don’t freeze in winter or overheat in summer is not the unreasonable or radical position.

Those who would risk winter and summer power outages to achieve an insignificant reduction in carbon emissions should be treated with at least the same skepticism as those who want to keep power readily available.

I am a mother of three (now adults) from Manchester, a former co-chair of the Manchester NAACP Education Committee, and a supporter of school choice. Let me tell you why.

I am a mother of three (now adults) from Manchester, a former co-chair of the Manchester NAACP Education Committee, and a supporter of school choice. Let me tell you why.