The first two weeks of September have seen a noticeable increase in positive tests for the SARS-CoV-2 virus in New Hampshire, coinciding with an increase in testing and the reopening of schools and colleges. Yet hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 have continued to decline during this time, state data show.

Media reports have tended to highlight the increase in positive test results while giving less attention to the continued downward trend in hospitalizations and infections. The significant increase in tests given per day has gone largely unnoticed.

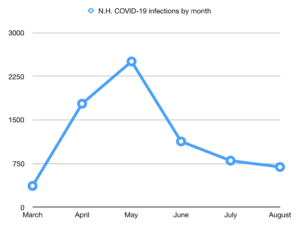

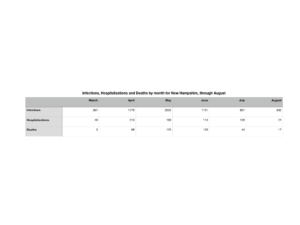

New Hampshire recorded 439 new infections from Sept. 1 through Sept. 14, after recording 692 new infections in the month of August. If infections continue at the same rate through the rest of the month, the state would see approximately 941 infections for September. That would represent a 36% increase over the previous month.

The increase in infections is partly explained by a sizable increase in testing. The state recorded an average of 3,027 tests per day in August. So far this month, the state has recorded an average of 3,575 tests per day, an 18% increase.

The increase in testing can explain some but not all of the rise in infections. Some additional spread appears to be occurring. That was to be expected with the reopening of schools and colleges. The notable development is that hospitalizations and deaths have continued to fall as infections have risen.

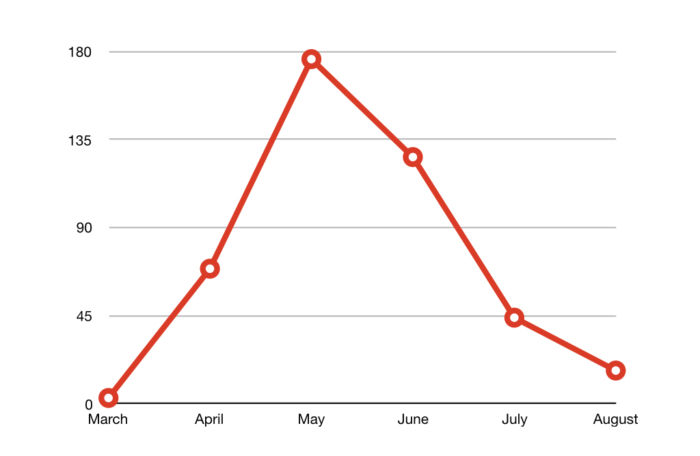

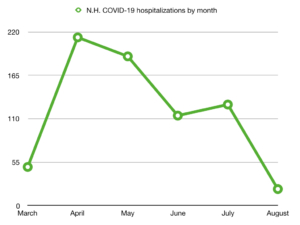

In the first two weeks of September, the state recorded only seven new hospitalizations and four deaths.

The state recorded 21 new hospitalizations in August. If September’s trend continues for the rest of the month, the state would finish September with a 33% decline in hospitalizations from the previous month.

At the end of August, the state’s COVID-19 hospitalization rate was 10% (meaning that 10 percent of all people who had contracted the virus since testing began in the spring had been hospitalized). By September 14, the hospitalization rate had fallen to 9.3%.

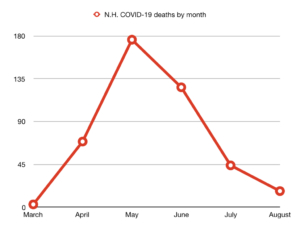

In August, the state recorded 17 deaths, a 61% drop from July and the lowest monthly total since the state began recording COVID-19 deaths in March. In the first two weeks of September, the state recorded only four deaths.

If this trend continues, the state would end September with only 8 deaths, for a 53% decline from the previous month. That would be the second straight month in which COVID-19 deaths fell by more than half.

These numbers don’t prove that bad numbers won’t come later this fall. Some schools are just reopening, and the weather is only beginning to turn cool. It’s possible that infections will continue to rise into the fall, and hospitalizations and deaths will begin to track with that increase.

But September’s numbers so far are not alarming. Two weeks after a large rally for President Trump in Londonderry (Aug. 28) and Bike Week in Laconia (Aug. 22-30), the state has not identified an outbreak connected to either event. And the rise in new positive test results has not coincided with an increase in cases severe enough to cause either hospitalization or death.

The next few weeks will give us a better picture of the effect of those events and of the reopening of schools and colleges. But for now, September is looking better than many people expected.