When the governors of Florida and Georgia announced that they would reopen their economies, the predictions of mass mortality were immediate. In April, a writer for The Atlantic hysterically labeled Georgia’s reopening plan an “experiment in human sacrifice.”

In the weeks that followed, the mortality surges never happened.

Digging through COVID-19 mortality data this week, we noticed something that to our knowledge had not previously been highlighted. There have been fewer COVID-19 deaths in Florida, Georgia and Colorado combined (three states criticized for opening “too early”) than in New York nursing homes alone.

The absence of a mortality surge is finally getting the attention of network TV news and other national media. ABC News’ lead medical reporter Eric Strauss tweeted on Thursday, “JUST IN: @ABC looked at 21 states that eased restrictions May 4 or earlier & found no major increase in hospitalizations, deaths or % of people testing positive in any of them. [SC, MT, GA, MS, SD, AR, CO, ID, IA, ND, OK, TN, TX, UT, WY, KS, FL, IN, MO, NE, OH.”

Politico Magazine on Thursday published a long essay on Colorado, “the blue state that gambled on an early reopening.”

Colorado’s Democratic governor, Jared Polis, “moved to lift stay-at-home orders not only well before other Democratic-leaning states, but ahead of Republican-led Georgia, Florida and Texas,” Politico pointed out. And he had a plan.

Polis, “instead of looking most closely at case and death counts, which lag behind the reality on the ground… focused on bringing down the virus’ transmission rate from one person infecting up to four others to one person infecting just one other person, which the state managed in April. As officials added thousands of temporary hospital beds, the governor also closely tracked the daily hospitalization rate, which had begun to slow by the time he made his April 20 announcement.”

Using realistic metrics that indicated how much of a public threat the virus was, Polis determined early that reopening could be done without causing an unmanageable surge in transmissions or hospitalizations.

The result?

“An average of just 4.64 percent of people tested over three days ending Tuesday were positive for COVID-19. That’s the lowest since the state started tracking a three-day average of positive cases back on March 10,” Colorado Public Radio reported on Wednesday.

Colorado is still experiencing outbreaks in places like meat packing plants, prisons, a grocery store, and an office. But those outbreaks are not spiking overall transmission rates. “While outbreaks continue to occur, overall, the number of new cases reported to the state continues to drop,” the Colorado Public Radio report concluded.

Many Colorado businesses have been operating under capacity restrictions. But by identifying meaningful, reasonable metrics to guide the reopening, the state was able to begin its economic recovery early and eliminate some of the uncertainty for business owners.

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu has managed a difficult challenge with great skill and has listened to business owners, adjusting some regulations and guidance after seeing how harmful it could be. Bringing business and community leaders into the decision-making process by creating task forces has allowed a greater degree of citizen input and prevented some of the more restrictive regulations seen in other states.

Yet it is not clear what data are guiding New Hampshire’s approach and what the precise goals are. Business owners and employees remain frustrated because the state has offered little clarity on how emergency rules are to be lifted.

Initially, the state’s emergency measures were focused on ensuring adequate hospital capacity in case of a surge of COVID-19 cases. The curve flattened weeks ago and the anticipated surge never happened. This week the governor ordered 10 of the state’s 14 overflow hospital sites closed.

Yet the governor also extended his emergency order and the stay-home order this week. People see the numbers going down, the curve flattened, but emergency orders and restrictions remaining in place.

Asked on Tuesday what data the state is using to guide its decision-making, Health and Human Services Commissioner Lori Shibinette struggled to give a coherent answer. After being asked several times about the state’s declining infection rate, she seemed to say that the state’s goal was to prevent every long-term-care facility employee from getting infected.

“Those caregivers are part of our communities. So, as long as there’s still COVID circulating in our communities, there is always a risk of bringing it into a nursing home. And there is always a risk of negative outcomes,” she said.

Ensuring that no long-term-care facility staff become infected cannot be the goal. It’s an impossible target.

The governor on Friday offered some clarity, saying that “flattening the curve” to keep hospital capacity available remains the goal. With the curve already flattened, the state is striving to prevent a new surge from overwhelming the hospitals, he said.

The governor added in response to a question that the guiding data are the percent positive and the hospitalization rate. Yet state officials still have not explained exactly what the state’s target numbers are.

Without clarity on the state’s targets, people will continue to be frustrated and anxious, and business owners will be unable to plan.

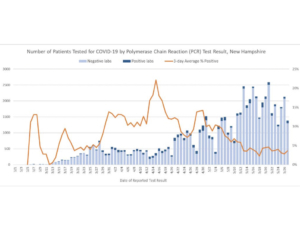

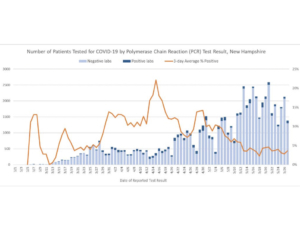

As the state’s own chart below shows, New Hampshire’s rate of positive COVID-19 test results has trended downward for weeks and is below 5%, about the same as Colorado’s. The state has 110 hospitalized COVID-19 patients, well below capacity. By any of the standard metrics, the state’s numbers have been trending in the right direction for weeks.

Yet economically crippling restrictions on business and personal activity remain, imposing enormous costs. In April, the state counted 101,490 newly unemployed Granite Staters, for an unemployment rate of 17.2%. It’s worse up north. Coos County’s unemployment rate hit 22.6% and Carroll’s 24.3%.

There’s little reason to believe that, say, Coos County retail and restaurant employees have to lose their jobs to protect the state’s vulnerable population, most of whom are elderly residents of long-term care facilities and individuals with co-morbidities.

The overwhelming majority of New Hampshire’s coronavirus deaths (78%) have occurred in long-term care facilities, and 77% of deaths were associated with a cluster, meaning three or more cases in a single workplace or facility.

Community transmission accounts for 20% of New Hampshire hospitalizations and 13% of deaths. Clearly, a vulnerable individual can contract the virus out in the community, get sick, and die. But the available data suggest that this risk is very low and that these individuals can be protected through less drastic measures.

Japan offers a case study. On Tuesday, Science magazine reported that Japan had ended its state of emergency, having achieved its public health goals without ever issuing a lockdown.

“It drove down the number of daily new cases to near target levels of 0.5 per 100,000 people with voluntary and not very restrictive social distancing and without large-scale testing. Instead, the country focused on finding clusters of infections and attacking the underlying causes, which often proved to be overcrowded gathering spots such as gyms and nightclubs.”

Japan lacks the legal authority to impose mandatory lockdowns, so instead it focused on educating the public about mask-wearing and avoiding the “three Cs”—closed spaces, crowds, and close-contact settings.

These are specific, attainable, and goal-oriented guidelines. They are easy for the public to understand, and they allow business owners and employees to participate in the process. If the state publicized that the economy could fully open when X and Y metrics were met, and initiated a high-profile publicity campaign to encourage broad public participation in reaching those goals (by wearing masks, social distancing, not forming large crowds, etc.), everyone would have clear goals they could work toward together.

Instead, the public remains in a state of suspense, waiting anxiously each week for new reopening guidelines segregated by industry.

As we’ve recommended before, the state’s focus should be on encouraging socially responsible behavior. Many businesses that are closed or partially closed now can open responsibly, posing little risk of creating mass outbreaks, if the state devotes its resources to education, instruction, and assistance rather than categorical business lockdowns.

The longer the state continues this slow lifting of restrictions, the worse the economic damage will be and the more frustrated members of the public will become.