Note: This column was first published in the New Hampshire Union Leader July 5, 2019.

By Andrew Cline

Reading through the state budget passed and vetoed last week, I was struck by how many provisions had gone either unreported or lightly reported. The people’s elected representatives had just passed a $13 billion budget, and the people, excepting a handful of insiders, had little idea what was in it.

For example, the budget:

- raised the tobacco-purchase age from 18 to 21 and changed the tobacco tax to a nicotine tax so the state could legally tax e-cigarettes (which sometimes contain nicotine but never tobacco);

- repealed the state law prohibiting state funding for abortions;

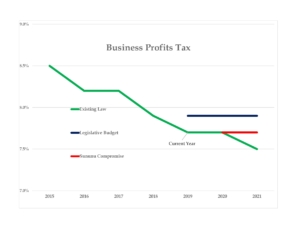

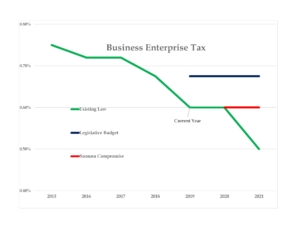

- raised this year’s business tax rates and applied the higher rates to taxes already paid this year, effectively imposing a retroactive tax increase on New Hampshire businesses.

It isn’t just the budget. Whole portions of the legislative session passed in relative darkness.

In the last year, the Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy’s email newsletter has broken several political news stories. There was no media conspiracy to hide the news. Too often, there simply was no media.

In some newsworthy committee meetings, the Bartlett Center had the only non-lobbyist with a pen and a publication there. Other times, we were the only ones questioning government officials about stories that weren’t the biggest topics of the week.

Our government watchdogs have been forced by collapsing profits to lay off the reporters who once kept the public informed. In their absence, the public knows not what transpires in its own state capital.

At the turn of this century, the press room at the State House was full, with several organizations sending multiple reporters. Even smaller papers like Foster’s Daily Democrat had a capital reporter.

If you sent the press room a dozen doughnuts today, reporters would fight over who got to take home the leftovers.

With so few journalists, legislators are doing their business with minimum scrutiny. The biggest issues get covered, but thinly compared to the past, and many issues go unreported.

It’s worse in cities and towns. Reporters, once commonly seen sitting in the back rows of public meetings or roaming the halls of town offices, have gone the way of the shoe shine boy.

The results are self-evident. Governing magazine reported in 2015 that dwindling media coverage of state government led to more pack reporting (reporters covering the same big stories the same way) and more click-driven reporting.

Recent studies show that less media scrutiny leads to higher government spending. In a 2018 study, professors at the University of Notre Dame and the University of Illinois at Chicago looked at 1,596 newspapers in 1,266 counties from 1996 to 2015. They found that municipal borrowing costs increased in communities that lost newspapers.

“You can actually see the financial consequences that have to be borne by local citizens as a result of newspaper closures,” a co-author said.

A similar study in Japan found that an increase in newspaper market share was associated with a drop in public works spending.

Other studies have tied newspaper losses to reductions in voter participation and civic engagement. Wallet Hub just ranked New Hampshire the most patriotic state, with civic participation being a top factor. If we abandon local journalism, we should expect that ranking to fall.

More journalists make government more accountable and citizens more engaged. Some conservative readers might counter, “But not if all the journalists are liberal!”

Media bias is a problem, but ending bias by killing newspapers is like ending Pledge of Allegiance protests by abolishing the NFL.

It’s better to have an active news media, even biased, than to have no one keeping an eye on government.

Don’t take my word for it. Ask our Founding Fathers.

During the American Revolution, reliable information was scarce and enormously valuable. In New Hampshire, patriot leaders constantly encouraged each other to read the newspapers. Letters from New Hampshire’s three signers of the Declaration of Independence include the following:

Josiah Bartlett to John Langdon, Sept. 30, 1776: “There is no news here, more than you will see in the publick prints.”

William Whipple to John Langdon, July 8, 1776: “I must refer you to the papers for news.…”

Matthew Thornton to Meshech Weare, Nov. 12, 1776: “For better and further information and news, I must refer you to the newspapers, and you won’ t find more falsehood in them than is passing through this city.”

William Whipple to John Langdon, June 10, 1776: “Colonel Bartlett sends you newspapers.”

Citizens cannot check government power if they abandon the organizations that expose what government is doing. This Independence Day weekend, commit a radical act of American patriotism. Subscribe to your local newspaper.

Andrew Cline is president of the Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy, New Hampshire’s free-market think tank.