Since the turn of the 21st century, the percentage of freshmen New Hampshire legislators with a record of public service in their community has fallen significantly, a new UNH study shows. Instead of having served on a select board or the board of a local non-profit group, today’s legislators are increasingly public service rookies.

The study, “All Politics, No Longer Local? A Study of the New Hampshire House of Representatives, 2001–2021”, which I co-wrote with UNH Political Science Professor Dante Scala, shows that local ties in the New Hampshire House have declined over the last two decades.

“In brief, we conclude that while the latest generations of New Hampshire state legislators still often have significant local governing and civic experience prior to their service in the General Court, they have been less likely over the past decade to bring that type of experience with them to the legislature,” we wrote.

We observed this decline among both men and women, as well as Democrats and Republicans.

We examined new House members’ biographies from the 2001–2002 to the 2021–2022 N.H. House (1,179 legislators in total), chronicling their experiences and backgrounds prior to joining the chamber.

Examining each decade separately, we found that the average proportion of new legislators with local government experience in a given year across the first decade of study (2001–2011) was 50%.

This proportion dropped significantly in the second decade. From 2013–2021, the average proportion of new legislators with this type of experience was 43%—a 14% decline.

There was an even greater drop in civic experience. On average, 49% of new legislators in a given year had previous experience in civic groups during the first decade. This fell to 35% in the next decade—a 29% decrease.

Overall, the percentage of legislators with some form of local engagement, either in government or civic groups, shrunk between the two decades.

“In the 2000s, the participation rate was typically above 70 percent; in the last decade, however, the rate fell into the 60s and in some cases even lower,” we wrote.

After the 2020 elections, Americans for Prosperity State Director Greg Moore observed a sharp drop in legislators with local community service experience.

“You’ll find a lot fewer people who were school board members or city councilors or aldermen, and a lot more folks for whom this is their first entree into politics,” Moore said.

He attributes the shift to a change in the way candidates for state office are recruited.

“The real change is that there are now groups on the right and the left that recruit candidates who align with their views for these rep. seats and then help them win primaries,” Moore said. “Earlier, local party committees did the recruiting and recruited on the basis of experience and having won local elections.”

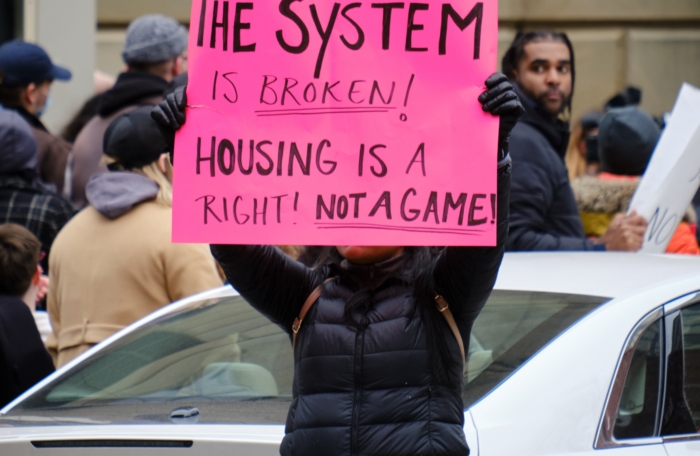

The result is that rather than a body composed of local volunteers, you get a legislature increasingly made up of activists who adhere to their party’s platform.

“What it means is that you end up with more representatives who are inclined to vote based on principles instead of being people pleasers,” Moore explained. “With that said, primary voters seem to respond to principled candidates versus those who reflect various factions in their community. This isn’t a bad thing, it’s just different from when I first started working with the New Hampshire Legislature 20 years ago.”

Elections at all levels have become increasingly nationalized. Although New Hampshire is still known for its local brand of politics, this research suggests that even the Granite State’s quintessential volunteer legislature has succumbed to national polarization.

While the study acknowledges that the typical state representative still often carries with them an element of local ties, the marked drops in previous local government and civic experience among newly elected members of the House suggest that the makeup of the lower chamber is undergoing significant changes.

And these structural changes have likely affected the House’s work. “If we take it that legislators’ backgrounds, at least in part, inform their political opinions and policy preferences,” we suggest in the study, “then the general decline in local governing and civic experience among new members of the New Hampshire House may have had an effect on the type of legislation coming out of the New Hampshire General Court.”

You can find the full study here.