“Very heavy taxes, are hurtful, because they lessen the increase of population by making the means of subsistence, more difficult.”

— John Adams, 1780

Last November, Massachusetts voters approved a so-called “millionaire’s tax.” It raises the state income tax from 5% to 9% for incomes of $1 million or more, an 80% tax increase.

Four months later, the Massachusetts Society of Certified Public Accountants is sounding an alarm.

After surveying 270 member CPAs, the society in March released a paper titled “Massachusetts is Losing Residents and it’s Getting Worse: Can Tax Policy Changes Mitigate Outmigration?”

The survey of Massachusetts certified public accountants found that:

-

82% of CPAs surveyed indicated that their high-income clients have expressed plans to leave Massachusetts in the next 12 months. Florida and New Hampshire are overwhelmingly the most popular choices for relocation. While some may argue that a move to Florida is driven by a desire for better weather and a different lifestyle, the fact that the second most popular destination is New Hampshire suggests that people want to stay in the area but may be motivated instead by a lower cost of living, including a lower tax burden. Furthermore, New Hampshire is set to repeal its Interest and Dividends Tax by 2026, which would make a decision to relocate even more appealing.

-

61% of respondents indicated that tax policy is the primary reason their clients are considering leaving the Commonwealth in the next 12 months.

-

An additional 39% of CPAs indicated that tax policy is a consideration for relocation.

-

0% of respondents indicated that tax policy is not a factor in the decision for high-income taxpayers to relocate.

-

More pointedly, half of CPAs said that the new Millionaire’s Tax specifically is the primary reason their clients are considering a move in the next 12 months.

“Some may have been willing to bear Massachusetts’ tax policy in the past, but moving from a five to nine percent income tax rate is an unprecedented 80% rate increase,” the report concluded. “That will undoubtedly inspire affected Massachusetts residents to reconsider their primary residence.”

New Hampshire Business Review reached a similar conclusion after interviewing New Hampshire real estate agents.

Outliers

The Massachusetts CPAs call Massachusetts an “outlier” in the region for its extremely high tax rates and complex tax code.

“Being an outlier makes it more difficult for the Commonwealth to compete with its regional neighbors and on the national landscape when it comes to attracting jobs, residents and capital investment, but it also violates basic tax principles of neutrality and economic efficiency,” the CPAs wrote.

“The current tax code introduces complexity and incentivizes opportunities to use a domicile change as a tax planning tool, which creates a host of unintended consequences for the state. Before the Millionaire’s Tax Massachusetts maintained a competitive edge in our region with the relatively low, flat individual income tax rate, which helped mitigate other issues such as the uniquely burdensome short-term capital gains tax rate and estate tax. Unfortunately, that is no longer the case.”

Those are words New Hampshire policy makers should always remember.

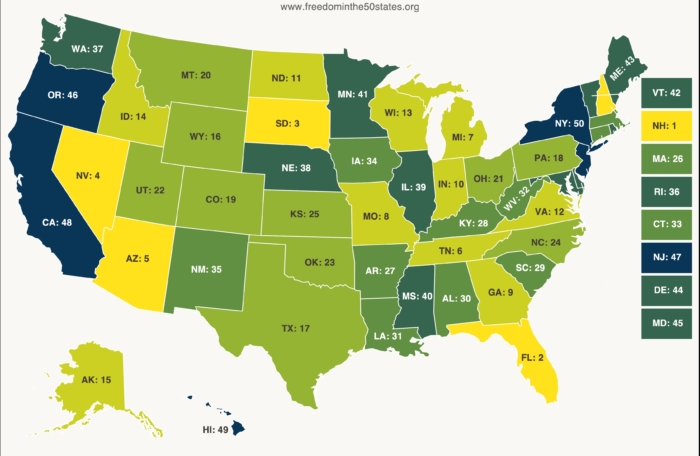

New Hampshire is an outlier too, in the other direction. Our lower tax burden has helped to make our state the economic envy of the region, a continental marvel and a haven for tax refugees.

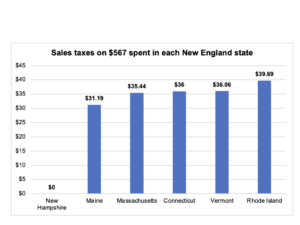

New Hampshire ranks 47th in state tax collections per capita, just a hair worse than Florida, according to a Tax Foundation ranking released this month.

How do the other New England states fare? They’re all in the top 20.

Vermont is No. 1, Connecticut 3, Massachusetts 7, Maine 15, and Rhode Island 16.

New Hampshire collects very little tax revenue per person, compared to our neighbors, and yet we have the region’s lowest poverty rate and a booming economy. And we’re stealing population from the high-tax jurisdictions around us. Funny how that works.

WalletHub, in an analysis also released this month, ranked New Hampshire 48th (third best) in tax burden. Maine and Vermont ranked in the top five, and the rest of the New England states were in the top 20.

Migration patterns don’t precisely align with tax burden rankings because people aren’t 100% economically motivated, but there’s a tremendous amount of overlap. In 2022, Americans did tend to move from high-tax to low-tax states, as usual, according to several different data sets, including the Census’ own.

The top in-migration states in 2022 were low-tax Florida, Texas, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee, while the top out-migration states were high-tax California, New York, Illinois, New Jersey and Massachusetts, according to the list compiled by the National Association of Realtors.

Just-released Census data show that six of the top ten counties in the United States for population growth from July 2021-July 2022 were in Texas. The counties that lost the most people were Los Angeles County and Cook County, Illinois, Axios reported.

The Massachusetts CPAs note in their report that a huge tax rate increase on people who are most able to move, passed right as the rise of remote work has made people less tied to their location, is a recipe for exodus.

Likewise, a big tax rate cut on the same people, at the same time, would be a strong attraction. Strategically, this year would be the perfect time to accelerate the phase out of New Hampshire’s Interest & Dividends tax.

Scheduled to phase out over the next four years, the tax remains for now a signal to high-wealth individuals that Florida would be a better relocation destination.

Like any number of high Massachusetts taxes, the I&D tax is a disadvantage. It weakens New Hampshire’s competitive position and serves as a disincentive to move, or stay, here.

It’s currently on schedule to be phased out by 2027. The House Finance Committee has recommended moving that date to 2025. Were the state to do that, or nix the tax entirely this year, it would not be lost on high-income individuals, retirees and anyone else with income from interests or dividends that New Hampshire’s tax burden is falling as Massachusetts’ is rising.

New Hampshire is not listed among the seven states that truly have no income tax. Eliminating the I&D tax would put us on that list and make New Hampshire an even more attractive destination.

Some might say that we don’t have to make ourselves more competitive if Massachusetts is making itself less competitive. But state tax competition is no longer just regional.

The rise of remote work makes it even easier for people to shop for a low-tax place to live, regardless of where their employer is located. And the world’s increasing wealth makes it easier than ever for investors, entrepreneurs, retirees and others to move to favorable jurisdictions.

The Massachusetts CPAs point out that when high-income residents leave Massachusetts, they take their community involvement and charitable giving with them. Making New Hampshire more attractive to these increasingly mobile people benefits not just New Hampshire’s economy, but our communities too.

While Massachusetts is pushing higher-income residents out, New Hampshire has an opportunity to turn their attention away from Florida and toward the Granite State.