The Merrimack County Superior Court this week dismissed a lawsuit brought by Deb Howes, president of the American Federation of Teachers-New Hampshire (AFT-NH), challenging the constitutionality of New Hampshire’s Education Freedom Account (EFA) program, the state’s largest school choice program.

Howes challenged the EFA program on three grounds: (1) The EFA program violates Part II, Article 6-b of the N.H. Constitution by allocating lottery money to EFAs, (2) the use of Education Trust Fund dollars for EFAs violates RSA 198:39 regarding distribution of funds from the Education Trust Fund, and (3) the EFA program represents an unlawful delegation of governmental duty to a private entity (Children’s Scholarship Fund New Hampshire).

Presiding Justice Amy L. Ignatius granted the New Hampshire Department of Education’s motion to dismiss on all three grounds.

On the claim that lottery money is spent on EFAs, Justice Ignatius concluded that Howes had not and could not demonstrate a violation.

Part II, Article 6-b of the New Hampshire Constitution reserves lottery revenue “exclusively for the school districts of the state.” Lottery revenues are deposited into the Education Trust Fund. But so are revenues from eight other sources. In the 2022 fiscal year, lottery revenues comprised only $125 million of the $1.145 billion in the Education Trust Fund. Howes was unable to show that any lottery revenues were included in the $9 million transferred to the EFA program. Lottery money comprised only 0.01% of the Education Trust Fund, and EFA spending could easily have come from the other 99.99% of the fund.

On the claim that the Legislature violated RSA 198:39, governing distributions from the Education Trust Fund, Ignatius ruled the claim moot since legislators had added a provision expressly allowing distributions to scholarship organizations that manage the EFA program.

On the claim that the EFA program constitutes an unlawful delegation of legislative authority to provide an adequate education, the court was unpersuaded. Howes had claimed that the EFA program was created to remove children from the public school system for the purpose of eliminating the state’s obligation to provide children an adequate education, and that it prohibited students from obtaining an adequate education. Ignatius dismissed the claims, countering that neither was logical. Parents who choose an EFA lose nothing, Ignatius pointed out. If parents choose an EFA, the state is not obligated to provide their children with a public school education while they participate in the EFA program, she noted. But that is the family’s choice. If they choose later to enroll their children in a public school, their participation in the EFA program does not block this option. Therefore, participation in the EFA program in no way prohibits families from accessing a public school education.

In response to the court’s dismissal of her claims, Howes said, in part:

The Legislature should be focusing far more time and resources on the needs of the 160,000 Granite State public school students who deserve a robust curriculum and fully staffed schools, not on the 4,000 students whose families choose to take state-funded vouchers. Vouchers have exacerbated an already disparate burden placed on local property taxpayers to fund the basic right to a quality public education. Every Granite State public school should be a safe and welcoming place where students have the academic challenge and support they need to thrive.

This statement flies in the face of reality on several fronts.

First, the Legislature does focus “far more time and resources” on the 160,000 students enrolled in district public schools versus the roughly 4,000 students with EFAs. In the 2021–22 academic year, total spending (state, local, and federal) on New Hampshire public schools exceeded $3.5 billion. Total expenditures per pupil exceeded $23,000.

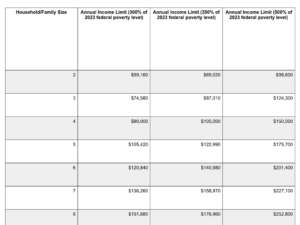

The EFA program is tiny in comparison. The court pointed out that, from the $1.145 billion Education Trust Fund, a mere $9 million was transferred to the EFA program in the 2022 fiscal year. The state’s estimated cost in the 2024 fiscal year is just $22 million, a tiny fraction of the more than $3.5 billion spent on public schools. EFA expenditures per pupil average just $5,255 versus more than $23,000 for public schools.

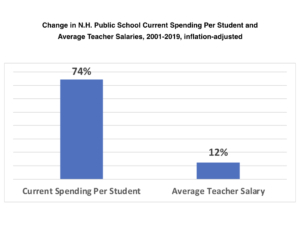

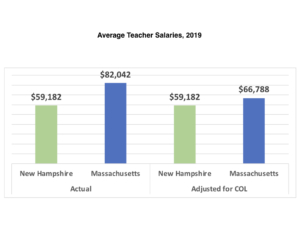

Average district public school spending in New Hampshire is 14.4% above the national average, while teacher pay is 5.3% below the national average. Moreover, district public school enrollment fell by 14% from 2001–2019 (a loss of 29,946 students), while inflation-adjusted spending at district public schools ballooned by 40% ($937 million).

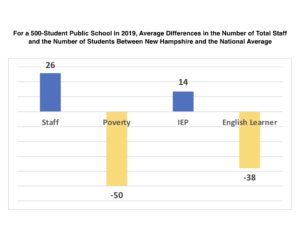

Far from being strapped for cash and staff, New Hampshire’s district public schools have never experienced higher funding despite continued drops in enrollment. Between the 2019–20 and 2023–24 school years, New Hampshire’s public schools experienced a 6.3% decline in enrollment (a loss of more than 11,000 students). New Hampshire experienced the nation’s largest percentage increase in district public school staffing relative to student enrollment from 1994–2022.

Additionally, as more families choose to access educational alternatives outside of their assigned district public schools, per-pupil funding for those who remain in the public schools only increases since local funding (which accounts for 60% of public education funding in New Hampshire) remains untouched by the EFA program.

From 2001–2019, inflation-adjusted public education spending per student increased by 66.8% in New Hampshire. By 2019, per-pupil public education spending in the state was 25.7% above the national average.

The state’s Education Trust Fund ended the 2023 fiscal year with a $148 million surplus. The long-term decline in the state’s school-age population has left the fund with such a big surplus that legislators have considered changing the funding formula so that such a large pool of money does not sit unused.

So, it’s untrue that the EFA program is draining money from district public schools. The state has a huge surplus of funds available for spending on public education even after increasing public school spending by nearly $1 billion, adjusted for inflation, in the first two decades of this century. And legislators in the most recent state budget further increased public education spending by $169 million during the two-year budget cycle and by a projected $1 billion over the next decade.

Again, it’s untrue that state spending on district public schools is declining at all, much less that it is declining because of EFAs. So, in addition to the legal arguments in this case being unfounded, the financial claims were as well.