A new UNH poll purports to show that Education Savings Accounts are unpopular in New Hampshire. That would be surprising because plenty of other survey data, including previous UNH polling, shows that ESAs (and school choice in general) draw more support than opposition.

One look at the wording of the UNH Survey Center’s poll question shows that it’s deeply flawed.

With public opinion polling, it’s critical to word the questions carefully and properly.

For example, if you ask “Do like cake,” you’ll likely get a different answer than if you ask, “Do you like high-fat, high-calorie baked dessert breads covered in artery-clogging icing?”

People know what cake is, so you don’t have to describe or explain it. But most people don’t know what Education Savings Accounts are (past UNH polling shows this). So it’s critical that they be described accurately so people can offer an informed opinion.

The UNH Survey Center has been careful with this question in the past. This time, it wasn’t, and the results were different than those produced by other surveys of ESA support.

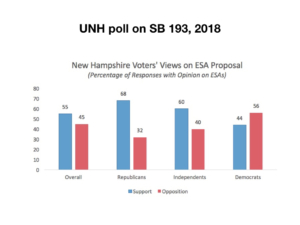

In 2018, the last time the Legislature considered an ESA bill, the UNH Survey Center offered an accurate description that informed the respondent. Even so, most people weren’t familiar with the concept. The pollster then tried to gauge the support only of those who said they had at least a little bit of knowledge about the legislation.

Here are the questions the UNH Survey Center asked in its February, 2018 poll:

“As you may know, the New Hampshire legislature is considering legislation that would create Education Savings Accounts, which would allow parents to receive a state-funded scholarship to use for education costs such as tuition, testing, fees, and books. If that child is not in their public school. How much have you seen or read about this bil, a great deal, a moderate amount, only a little, or nothing at all?”

“Supporters of the legislation say it will give parents more choice when it comes to their children’s education while opponents say it will take away state money that should be spent on public schools. Would you support or oppose this legislation or don’t you know enough about this to say?”

The first question correctly described ESAs as scholarships that could be spent on a variety of education expenses outside of a child’s assigned public school.

That poll found 40% support for ESAs, with only 33% opposed, 9% staying neutral and 18% saying they don’t know enough about the issue.

Contrast that with the March 2021 poll.

It asked this question:

“The New Hampshire Legislature is considering a bill that would create a voucher system, called “education freedom accounts” by supporters, that would give parents access to public dollars that could be put toward private schools (not colleges) for their children.”

That question generated the response that 35% support and 45% oppose.

But the question inaccurately describes the EFA program in SB 130.

First, it describes EFAs as “vouchers,” which is not true. A voucher sends money directly to an education provider. EFAs create savings accounts controlled by parents, who then get to decide which state-approved education services to purchase.

Second, it states only that the money goes to private schools other than colleges. That is misleading.

The EFA money does not go straight, or exclusively, to private schools. An EFA is a savings account that parents control, bounded by limits set in statute. Families could use the money for a long list of approved education expenses, including tuition at an out-of-district public school as well as a private school, tutoring, special education services, textbooks and curricula, tuition for individual classes at public and private schools as well as colleges, career and technical education, online classes, and more.

SB 130 also limits eligibility for EFAs to families with incomes of no more than 300% of the federal poverty level, would use only each student’s state adequate education grant, leaving local school funding untouched, and provides additional funding to public schools for each student who choses an EFA during the first three years of the program.

No one listening to the UNH pollster would know any of that.

When Education Savings Accounts and other forms of school choice are described accurately, polling shows that they tend to have strong support, particularly among lower-income and minority parents.

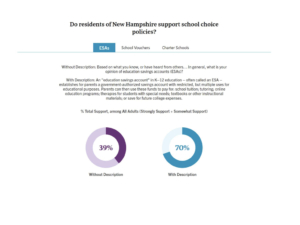

EdChoice has surveyed New Hampshire residents on this very issue. Its poll, conducted by Morning Consult, asks two questions.

In the first, it doesn’t describe ESAs. That question asks:

“Based on what you know or have heard from others, in general, what is your opinion of Education Savings Accounts?”

That question finds 39% support for ESAs, almost exactly what the UNH Survey Center found by inaccurately describing ESAs.

EdChoice, though, also asks a different question that accurately describes ESAs. It reads:

“An Education Savings Account in K-12 education — often called an ESA — establishes for parents a government-authorized savings account with restricted, but multiple uses for educational purposes. Parents can use these funds to pay for: school tuition; tutoring; online education programs; therapies for students with special needs; textbooks or other instructional materials; or save for future college expenses.”

When ESAs are properly described, support in New Hampshire shoots up to 70%.

Education Next, a project of Harvard University and Stanford University, regularly tests public support for school choice programs. Its most recent poll, in 2020, found:

- 51% of Americans support voucher programs in which government helps pay private school tuition costs for children, and only 36% oppose;

- 44% support charter schools, and only 37% oppose;

- 57% support tax-credit scholarship programs, and only 27% oppose.

Education Next did not ask about Education Savings Accounts. But its polling finds school choice options to be more popular than unpopular.

Another example of nationwide findings comes from the Associated Press, which just published the results of a survey that found more support than opposition for vouchers for low-income families.

The AP poll question was this:

“Do you favor, oppose, or neither favor nor oppose each of the following government-funded policies? * Give low income parents tax-funded vouchers they can use to help pay for tuition for their children to attend private or religious schools of their choice instead of public schools.”

Among K-12 parents, 46% favor vouchers for low-income students, and 28% oppose.

The March 2021 UNH poll was the only one here to find opposition exceeding support for school choice. There’s a reason for that. Its question was bad.

The UNH poll can’t possibly offer an accurate reflection of the public’s views on SB 130’s EFA program because it inaccurately described the program. The only New Hampshire poll to provide a good description of EFAs found 70 percent support for them.

Policymakers considering this issue shouldn’t give any weight to a poll in which the topic being polled was so wrongly described.

I am a mother of three (now adults) from Manchester, a former co-chair of the Manchester NAACP Education Committee, and a supporter of school choice. Let me tell you why.

I am a mother of three (now adults) from Manchester, a former co-chair of the Manchester NAACP Education Committee, and a supporter of school choice. Let me tell you why.