Improving Outcomes through Choice

August 2015

Alicia Humphrey

Summary: Despite a recent shift toward national control over education policy, New Hampshire has implemented a variety of measures designed to embrace localization and flexibility. Some of the policies that have arisen include a new learning model, raised teacher quality, promotion of charter schools, and a raised dropout age. Data shows that these state-based innovations emphasizing school choice have led to increased success for New Hampshire public schools as compared to the state under national mandates.

Americans have become accustomed to viewing public education through a national lens. In the past, most power was left to local schools and politicians. However, since the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1950 and continuing to the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 and the Department of Education’s Race to the Top initiative of 2009, the federal government has taken and maintained increased control over schools through mandates, incentives, and funding. Although these initiatives represent sincere efforts to improve a struggling national public education system, the reality is that increased federal oversight often has the opposite effect by complicating matters with complex rules and regulations.

Once given the opportunity by President Barack Obama in 2013, New Hampshire, along with a majority of states, opted out of the unrealistic requirements of No Child Left Behind, leaving the state much freer to improve its education system on its own terms. New Hampshire has been quite successful in its attempts to reform due to a core recognition of the necessity of school choice and the rejection of a ‘one size fits all’ approach to education. To date, New Hampshire has quite successfully taken reformation of its public school system into its own hands through an innovative new learning model, raising teacher quality, promoting charter schools, and raising the dropout age, just to mention a few examples.

Student Focused Learning Models:

One of New Hampshire’s educational innovations is the new competency-based learning model.[1] Although this model exists in conjunction with the Common Core standards that largely govern what is taught, it certainly represents a move toward local flexibility and choice concerning how material is taught. In an unprecedented move amounting to nothing less than a complete revamp of the old learning system, New Hampshire has required statewide adoption of the competency-based model.

The change resulted from coordinated efforts including former Governor John Lynch, Former Education Commissioner Lyonel B. Tracy, and the State Board of Education in 2005. The new model replaces the traditional Carnegie Unit learning model based on passing versus failing letter grades. With the new model, learning will be based on competency broken up into individual objectives with mastery as the goal and time spent in the classroom as the variable instead of vice versa. The idea behind the new competency-based model is that it will remedy the Carnegie model’s lack of sensitivity to unique student needs due to its all-or-nothing approach to passing or failing a subject in a set amount of time.

Choices for Students:

The competency-based model is revolutionary in that it will allow students a choice to demonstrate mastery in a variety of ways and places other than standardized examinations in traditional classrooms—for example, through Extended Learning Opportunities (ELOs), Learning Seminars, and Place-Based Learning projects. These options have arisen organically in various New Hampshire schools due to the policy’s flexibility and focus on local control rather than federal oversight. ELOs are student-initiated in that they do not replace traditional schooling, but simply allow for it to be sculpted around each student’s interests; for example, students in the past have chosen to study everything from genetically modified organisms in farms in their communities to glassmaking and jewelry design in conjunction with their regular coursework.

Some schools have allowed students to participate in Learning Seminars for an entire year, in which they pursue and research a project of their choice centered on a problem they want to solve. Place-Based Learning projects are similar to Learning Seminars, but emphasize the importance of problem solving in the student’s specific community. Countless other opportunities like these have appeared in New Hampshire schools, most finding success due to their goal of individualizing and personalizing education for students through the more flexible and locally oriented competency model, which emphasizes choice over a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

Choice for Local School Districts:

It is not only students that have an increased choice now, but school districts as well; as of the 2008-2009 school year, districts in the state can choose to use the state’s competency models for English/Language Arts, Math, Science, and Work Practices (soon to include Arts and Social Studies), but these districts have the freedom to opt to design a more individualized one if they so choose. With this flexibility comes the freedom to change slowly; some schools have remained loyal to the more traditional, time-based practices of the Carnegie model, such as Oyster River High School in Durham. However, many more have been quick to adapt by creating unique opportunities for students to move at a more flexible and personalized pace, such as Milan Village Elementary School in Milan and North Country Charter Academy in Littleton and Lancaster.[2] Despite the risks that accompany these localized policies, the huge changes and successes under the competency model were made possible by the freedom, flexibility, and choice granted to schools to create programs to help students in very different communities and situations as opposed to more stifling national mandates.

Ensuring Teacher Quality:

This new learning model means little without excellent teachers to implement it; in response, the state has taken a variety of measures drawn to raise teacher quality. The state has created only five alternative certification routes other than the traditional method of certification at an undergraduate university or college: Alternative One requires a program of professional preparation in education along with a chairperson recommendation, Alternative Two is open for certified teachers from other states, Alternative Three requires a written exam and oral review, Alternative Four requires superintendent recruitment for teaching in high-need areas, and Alternative Five is an on-the-job training option that nevertheless requires a Bachelor’s degree.[3] This policy choice is compared to that of many other states, which often offer nearly double those alternative options with much looser requirements. For example, Kentucky has eight, including one which allows certification for anyone who has simply served in the armed forces for at least six years and holds a Bachelor’s degree in the subject area he or she wishes to teach with only a 2.5 GPA upon graduation.[4]

Although New Hampshire’s choice in policy may sound like a discouragement to many hopeful teachers-to-be, the unfortunate reality is that these alternative routes are just that: alternative. They often encourage lesser trained teachers to enter the profession as soon as possible, focusing on adults’ convenience instead of what is best for students. New Hampshire tackles this delicate issue by making the programs available for aspiring teachers who may not fit into the traditional mold, but simultaneously not overly plentiful and easy to complete. It is precisely the state’s ability to adopt these alternative certification methods

differing than those of many other states that has led to increased success in recruiting excellent teachers.

The more stringent method to becoming a teacher has had many benefits, one of those being a high level availability of excellent certified teachers; the 12.2 to 1 student-to-teacher ratio is one of the nation’s best and is extremely conducive to individualized attention and therefore improved learning and mastery for students inside the classroom. The financial benefit of teaching explains this in part; New Hampshire teachers make an average of about $50,245 a year or 117% of the state’s average income (an average of $3,900 more for those with Master’s degrees), making the job more prestigious and worthwhile, therefore attracting the highest quality teachers.[5]

School Choice:

It is especially in charter schools this high teacher quality is the easiest to see. These schools free of the bureaucratic red tape so common in the traditional public sphere—translating to increased teacher freedom in the classroom—have been shown to attract the best and brightest teachers from more prestigious and selective colleges, more so than in non-charter schools.[6] Furthermore, as charter schools possess less strict regulations concerning hiring practices as compared to traditional public schools, administrators have the ability to use their judgement to choose the best teachers for their individual schools and students. Largely because of these differences that allow for localized control and the flexibility to create schools that function best in unique communities, charter schools have been shown to be generally more effective than traditional public schools. Despite this success, spending per student for charter schools remains at a 40% of the money spent on traditional public schools.[7] In order to truly promote a culture of school choice, it is imperative to continue to increase funding to charters and responsibly reduce the accreditation burden for the schools in order to continue this success.

Addressing Dropout Rates:

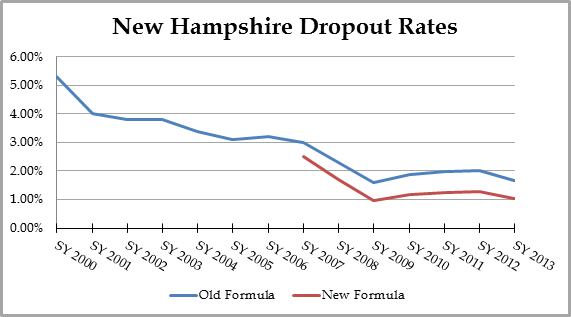

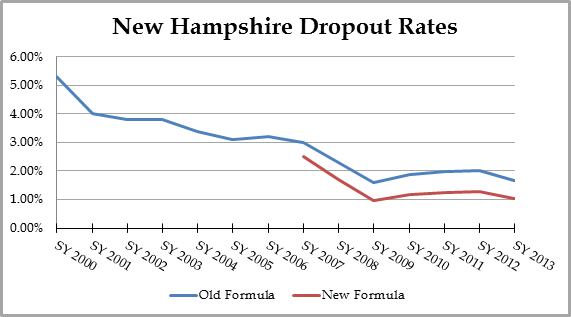

These developments again are meaningless unless students are habitually present in the classroom. In 2008, New Hampshire increased its state dropout age to 18 from the more nationally common 16. Although dropout rates were already on the decline in New Hampshire, only one year after this simple yet effective legislation, dropout rate began to plummet at a more rapid rate.[8] This trend of notable decrease post-legislation remains despite two different formulas used to calculate dropout rates in New Hampshire in the 2000s. [9]

Even with the exception of the only dropout rate rise in the past ten years occurring in 2011, the rate during that year is still the second lowest the state has ever seen.[10] With fewer students dropping out, New Hampshire saw an increase in graduation rates. In 2010, the state’s graduation rate was at 86.3%, ranking in the top nine of all U.S. states, compared to the national average of 78.2%.

Two years later, dropout rate was 1.26% compared to the national average of 7%.[11] It is no wonder that the state’s many innovations have been effective with a nearly complete student body present, passing, and eventually graduating from high school at one of the highest rates in the country. The state’s willingness and ability to stray from the norm and create policies that work for its students instead of adhering to the national status quo has created one of the most successful public education systems in the country.

Though it is difficult to entirely attribute the state’s success to the specific programs and initiatives previously described, it is impossible to deny the success of New Hampshire’s recent education policies as a whole; in 2013, the average eighth grade NAEP reading score was eight points above the national average and the math average was up by twelve, the average SAT score of students graduating high school was 1567 compared to the national average of 1498, and the four-year college graduation rate was 62% compared to the national average of 39%.[12]

Conclusion:

As New Hampshire has implemented countless creative education policies in the past few years that have led to these impressive results, the state has found that true success couples this progressive thinking with a focus on local authority over the schools and students they know best. Taking a lesson from the failed No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, New Hampshire’s initiatives have focused on grassroots feedback from students, teachers, and local leaders. State leaders have created truly effective and organic programs and policies centered on school choice as opposed to setting national goals with little flexibility or sensitivity to specific state needs. New Hampshire has demonstrated that although the ideas of innovation and localization may be construed to be opposites, in order to truly develop and advance, it is often necessary to embrace tradition.

Click here to download a pdf version of this paper

[1] New Hampshire Story of Transformation. New Hampshire Department of Education, 2014.

[2] Freeland, Julia. “From Policy to Practice: How Competency-based Education Is Evolving in New Hampshire.” Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation. Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation, May 2014.

[3] Alternatives for Certification. New Hampshire Department of Education, 2012

[4] Education Professional Standards Board Certification Division – Alternative Route Option 5. Kentucky Department of Education, 2015

[5] New Hampshire Story of Transformation. New Hampshire Department of Education, 2014.

[6] Finne, Liv. “An Option for Learning: An Assessment of Student Achievement in Charter Public Schools” Washington Policy Center, Jan. 2011.

[7] New Hampshire Center for Innovative Schools, www.nhcharterschools.org/home/index.php/stats-charts-graphs

[8] Bosse, Grant. “NH Drop Out Rate not dropping as quickly as government claims”, New Hampshire Watchdog, 09 Mar. 2011

[9] Dropouts and Completers, Data Collection and Reports. New Hampshire Department of Education, 2012.

[10] Bosse, Grant. “NH Drop Out Rate Jumped in 2011.”. New Hampshire Watchdog

[11] New Hampshire Story of Transformation. New Hampshire Department of Education, 2014.

[12] New Hampshire Story of Transformation. New Hampshire Department of Education, 2014.