On Monday, March 29, New Hampshire became the first New England state to make at least half its population eligible for a COVID vaccine, according to an estimate by the Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy. Two days later, on the last day of March, it became the first New England state to make at least two-thirds of its population vaccine eligible.

In March, New Hampshire and Connecticut quickly accelerated their vaccine eligibility, trading places for the most rapid expansion. Connecticut made approximately 45.7% of its population eligible on March 19 when it allowed sign-ups for people aged 45 and older. New Hampshire opened registration for residents aged 40 and older 10 days later, then opened registrations for ages 30 and older on March 31.

Since state vaccination programs began, they typically have been ranked by the percentage of their population that has been fully vaccinated. Another method is to measure the percentage for whom a vaccine is available. Both measures have problems, and both offer useful insights into a state’s vaccine rollout.

The biggest problem with judging a state by the percentage of its population fully vaccinated is that state governments don’t mandate vaccination; their responsibility is to make vaccines available.

Another problem is that a sizable, though declining, level of vaccine reluctance persists, particularly in more rural and Republican-leaning states, some data suggest.

Measuring a state government’s success by the percentage of the population that got the vaccine is to give credit or lay blame in part for factors that are beyond the state bureaucracy’s control.

Judging states by the percentage of the population that has access to a vaccine could be a better measure of the state government’s distribution program. However, this measure also is affected by public behavior and demographics.

If large portions of the earliest eligible groups decline vaccination because they are skeptical or fearful of the vaccine, that can make more doses available more quickly for later groups. If a state’s population is heavily skewed toward one end of the age spectrum, that will also affect the percentage eligible.

New Hampshire’s median age is 42.9, almost two years higher than Connecticut’s (41). That gives New Hampshire an edge over Connecticut on this metric. But Maine’s median age is 44.7. Vermont’s is the same as New Hampshire’s (42.9). Rhode Island and Massachusetts are the youngest New England states, with median ages of 39.9 and 39.5, respectively.

Another potential complication is that declaring eligibility is not the same as making the vaccine available. States can open sign-ups, but those are good only if the system is granting quick and easy access to appointments where vaccines are available.

Ultimately, states are responsible for creating a functioning distribution system that provides residents with the opportunity to obtain a vaccine. Once that system is functioning efficiently and effectively, states can encourage vaccination, but they do not conscript people into the vaccination program.

That being the case, looking at the percentage of the population that has access to the vaccine can be a useful way of assessing a state’s competence in getting doses to people who want them. At this core task, New Hampshire has done extremely well. Sign-ups have proven relatively easy, wait times are not long, and vaccines are readily available for those who want them.

Though no state’s distribution system has been flawless, New Hampshire’s has managed to avoid major failures while providing relatively easy and effective access for eligible groups.

By basing eligibility primarily on age, followed by vulnerability, the state has prioritized high-risk individuals while maintaining an uncomplicated sign-up system.

Connecticut designed and maintained a similar priority system, based primarily on age and vulnerability. Both states have stuck with these systems amid criticism from some that race, ethnicity and income should be weighed more heavily.

At the close of the first quarter of 2021, Connecticut and New Hampshire led New England in making vaccines rapidly available for most of the population. Other New England states have lagged weeks behind.

Connecticut’s vaccine eligibility remained at age 45 and older until April 1, when it became the first New England state to offer vaccines to all residents ages 16 and older.

New Hampshire ended March with vaccine appointments available to anyone 30 or older, with its schedule set to open vaccine sign-ups for ages 16+ on April 2, just one day after Connecticut.

Every other New England state is scheduled to expand eligibility to ages 16+ more than two weeks later, on April 19.

Using U.S. Census data, the Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy estimated the percentage of each New England state’s population that was eligible for a COVID vaccine on March 31, the end of the first quarter of 2021. Based on the age groups that were being offered vaccines on that date, New Hampshire was in the lead, with 67% of its population eligible, followed by Connecticut at 45.7%, Vermont at 42%, Maine and Rhode Island at 25%, and Massachusetts at 23%.

In addition to prioritized age groups, states have made first responders and other “essential” workers eligible for vaccines. We used only age groups to estimate the vaccine-eligible percentage of the population because we did not have good data for dividing these workers by age.

Adding essential workers without adjusting for age would boost each state’s figures by a few percentage points, but adding those numbers without knowing the workers’ ages would double count many, if not most, of them, particularly in Connecticut and New Hampshire.

Discrepancy between eligibility and vaccination rates

Becker’s Hospital Review ranks states by the percentage of the population that’s been fully vaccinated. On March 31, the New England states ranked by that metric were:

Rhode Island 20.7%

Connecticut 20.5%

Maine 19.31%

Massachusetts 18.5%

Vermont 18.4%

New Hampshire 17.1%

Why would New Hampshire rank first in New England in eligibility but last in vaccinations?

A likely reason is that a relatively high percentage of the population has reported being reluctant to get the vaccine.

The most recent U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse survey for late March found that 57.5% of Granite Staters who have not yet been vaccinated say they will do so. That is the 15th highest rate in the country. Yet it puts New Hampshire below every other New England state.

Looking into the survey’s data tables shows that 15% of Granite Staters said they definitely or probably would not get the vaccine. That is below the national average of 17.2%, but it’s the highest percentage in New England. Rhode Island is next at 14.3%, followed by Maine at 13.2%, Connecticut at 10%, and Massachusetts and Vermont tied at 7.4%.

Although New Hampshire has rapidly expanded eligibility, making the vaccine available to more than two-thirds of the population by the end of March, a relatively high portion of the state’s population, relative to the rest of New England, is reluctant to be vaccinated.

The importance of persuasion

And that brings us to a point the Josiah Bartlett Center made last year about the importance of building trust for public health measures. Regarding business closures and mask mandates, we cautioned that mandates and restrictions can backfire if they cut against public opinion. They can cause resistance, making it harder, rather than easier, to achieve public health goals. The first step in pursuing public health goals during a pandemic is to explain to the public why changes in behavior are needed.

In a democratic republic, persuasion is the primary political currency. Where people pride themselves in being free to live their own lives on their own terms, government dictates can backfire, causing resistance and making it harder to achieve desired goals. This is true in public health as in all other areas of public policy.

New Hampshire has done its job on the distribution end, making the vaccines widely available and easy to obtain. To get the vaccination numbers up, the state next should devote additional resources to persuading Granite Staters to get vaccinated.

Mass vaccination is the path out of the pandemic. Though the state has made this point, the federal government’s conflicting messages have caused confusion and delay. A more energetic and high-profile state campaign to encourage vaccination would help bring up our vaccination rates and move us more rapidly back to normal, or as close to normal as we can get.

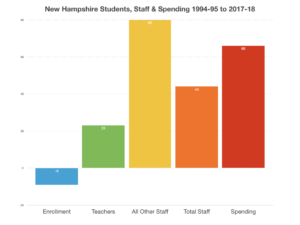

I am a mother of three (now adults) from Manchester, a former co-chair of the Manchester NAACP Education Committee, and a supporter of school choice. Let me tell you why.

I am a mother of three (now adults) from Manchester, a former co-chair of the Manchester NAACP Education Committee, and a supporter of school choice. Let me tell you why.