The weekend has arrived when Americans play for three days while politicians give speeches and issue press releases recognizing the economic contributions of the American labor movement.

Labor’s contributions are worth recognition. But have any politicians ever acknowledged that laboring in isolation produces nothing beyond basic subsistence? For labor to generate human progress, it has to be mixed with innovation. Yet we have no holiday for the innovators.

Our prehistoric ancestors labored for thousands of years with no economic advancement. The discovery of agriculture produced some wealth, but humans then labored on farms for millennia with only periodic and temporary spurts of economic growth. Technological innovations would sometimes lead to bursts of productivity that would improve living conditions, but those would fade relatively quickly.

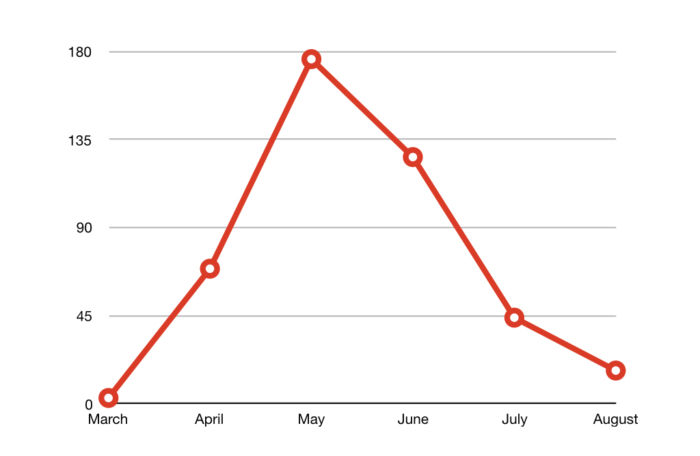

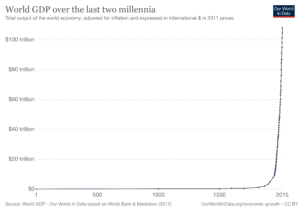

Not until the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution did humans suddenly begin to generate huge and sustained gains in living standards. This chart from Our World In Data shows how everything suddenly changed in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Scholars debate what caused this explosion of economic progress. But economist Deirdre McCloskey makes a compelling case that it was a change in human thought that gave birth to the miracle of modern growth.

A change in how people honored markets and innovation caused the Industrial Revolution, and then the modern world. The old conventional wisdom, by contrast, has no place for attitudes about trade and innovation, and no place for liberal thought. The old materialist story says that the Industrial Revolution came from material causes, from investment or theft, from higher saving rates or from imperialism. You’ve heard it: “Europe is rich because of its empires”; “The United States was built on the backs of slaves”; “China is getting rich because of trade.”

But what if the Industrial Revolution was sparked instead by changes in the way people thought, and especially by how they thought about each other?

She goes on…

Economists and historians are starting to realize that it took much, much more than theft or capital accumulation to ignite the Industrial Revolution—it took a big shift in how Westerners thought about commerce and innovation. People had to start liking “creative destruction,” the new idea that replaces the old. It’s like music. A new band gets a new idea in rock music, and replaces the old if enough people freely adopt the new. If the old music is thought to be worse, it is “destroyed” by the creativity. In the same way, electric lights “destroyed” kerosene lamps, and computers “destroyed” typewriters. To our good.

McCloskey has documented how the Enlightenment changed the way people think about work, creativity, invention, innovation, commerce and markets. Work and self-sufficiency were elevated in status, but so too were trade and commerce, finance and innovation.

In short, market capitalism was slowly recognized as a way for ordinary individuals to improve their station in life. And that changed humanity, unleashing an unprecedented era of sustained economic and cultural progress.

People began to realize that there were ways to advance from one social rank to the next, and those ways involved not working harder, but working smarter.

Enlightened American gentlemen in the late 18th century did not content themselves with continuing to work as their fathers had. They became obsessed with experimenting, tinkering and inventing. This was not confined to geniuses like Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.

George Washington experimented with new agricultural methods, invented a new type of threshing barn, and helped develop the American Foxhound.

The spirit of the age sparked a wildfire of imagination, leading to inventions from ordinary people who sought to improve their own lives and the lives of others.

In 1764, an illiterate weaver and carpenter named James Hargraves invented the Spinning Jenny, helping to spark the Industrial Revolution. He was a nobody, but he’s the one who turned his town into a boomtown.

Pennsylvania farmer Jacob Yoder invented the flat-bottomed boat in 1782. About 1785, uneducated Delaware businessman Oliver Evans invented the automatic flour mill.

The examples go on and on. A common theme is that the people who created the devices that allowed humanity to lift itself up from subsistence farming tended to be lowly tinkerers with little or no social status.

These tinkerers, inventors and innovators created the factories and machines that created the labor movement, which Americans are supposed to celebrate this weekend. Yet we have no holiday for the innovators. Their contributions are mostly forgotten, their achievements taken for granted.

Our culture assumes that prosperity and progress are humanity’s baseline. We have grown up in an advanced civilization with plentiful food, clothing and shelter, and with luxury goods so abundant that even people we consider poor have flat-screen TVs, smartphones and automobiles. We assume this is the way things always have been.

It was not. This is a recent human creation. Yes, labor made the factories, the railroads, the highways possible. But the innovators gave labor the tools with which they built our modern world. If we want to preserve the progress we’ve made, we should recognize and celebrate the innovators too.

Innovation, not labor, was the foundation of the Industrial Revolution. Labor, a critical component, came after. And it came because industrial life promised greater economic progress than life on the old family farm.

We can stimulate more progress by encouraging more innovation. If we forget its foundational contribution, we will only make additional progress harder.