UPDATE: This analysis has been updated to incorporate the Legislative Budget Assistant’s official tally of spending in the Committee of Conference budget.

The New Hampshire Legislature is scheduled to wrap up this year’s session on Thursday when the House and Senate convene to consider nearly 40 committee of conference reports hammered out by negotiators for each chamber, including the compromise version of the state’s two-year budget.

The conference committee budget would:

- Cut state General and Education Trust Fund spending by roughly $172.5 million, or 3.1%,

- Further lower business tax rates,

- Eliminate the Interest and Dividends Tax, making New Hampshire truly income-tax-free,

- Cut the statewide property tax while increasing aid to municipalities,

- Create Education Freedom Accounts to provide school choice to lower-income families,

- Prohibit the state from asserting, through employee training and K-12 education, that one demographic group is superior or inferior to others,

- Create a voluntary paid family leave program;

- Restrict abortions after 24 weeks,

- Give legislators the power to repeal a state of emergency declaration.

Overview

This year’s budget fight was unusual in that it did not center on taxes and spending, or indeed on fiscal issues much at all. In fact, House negotiators accepted the Senate’s version of House Bill 1, which contains the detailed spending for each state agency, with no changes. Instead, the field of debate shifted to House Bill 2, the trailer bill that contains the policy changes necessary to implement the state’s $13.5 billion budget plan over the next biennium.

The Senate-approved version of HB 1 would spend $5.4 billion from the state’s General Fund and Education Trust Fund in Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023. This represents a reduction in state General and Education Trust Fund spending of approximately $172.5 million, or roughly 3.1% of state spending. (The committee of conference made some changes to HB2, which will have a very small effect on this figure. To make sure we’re using official state numbers, we use totals from the Senate budget, as the Legislative Budget Assistant has not made an official tally of the Committee of Conference budget.)

That is an historic achievement and would be the second time in this century that state spending declined from one budget to the next. (The last time was in the 2012-13 state budget passed in 2011.) General and Education Trust Fund spending is the portion of state spending paid for by state revenues, such as business taxes, the tobacco tax, the Meals and Rooms Tax, etc. Total spending, which includes federal outlays, is $13.5 billion in this budget.

Tax Cuts for Everyone

Since 2015, Republicans at the State House have been pushing to lower the rates of the state’s two largest business taxes. The Business Enterprise Tax is a levy of payroll and operating expenses paid by all but the state’s smallest businesses. The Business Profits Tax is paid on profits, and it is largely borne by larger businesses. Six years ago, New Hampshire had among the highest effective corporate tax rates in the nation, prompting the GOP to take up business tax reform as a key step to improving the New Hampshire Advantage. Showdowns over business tax rate cuts led to impasses between Gov. Maggie Hassan and the Republican-led Legislature in 2015 and between Gov. Chris Sununu and the Democratic State House majorities in 2019.

This year, Republicans hold majorities in both chambers, as well as the governor’s office, and that has meant more business tax cuts. This year’s budget would lower the BET to 0.55%, down from 0.75% six years ago. The BPT would drop to 7.6%, down from a high of 8.5% six years ago. Cutting the state’s two largest taxes on Granite State employers by 27% and 10.5% over the course of four budget cycles is an impressive legacy for Republican lawmakers that has helped the state’s economy. Thanks in part to business tax reform, New Hampshire business tax revenues have exceeded projections every year since rates began to fall. The Granite State now boasts a growing economy, higher state tax revenue, and an unemployment rate of 2.5%. Business tax rates are just the first of many tax cuts contained in this budget.

HB 2 would also increase the filing threshold for businesses paying the BET from $200,000 to $250,000, meaning that many of the state’s smaller firms would no longer have any business tax liability, while delivering a small tax savings to all BET filers. This was an idea originally proposed by Senate Democrats as an alternative to Republican tax rate cuts, but was included in addition to the rate cuts.

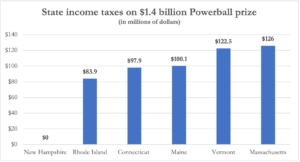

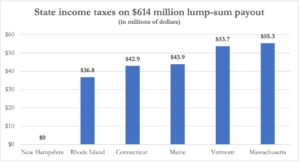

The budget deal begins to phase out the Interest and Dividends Tax entirely. This 5% tax on investment income above $2,400 hits hardest seniors who have planned to retire on their investment income. It has led critics to charge that New Hampshire has never been truly income tax free. The tax phases out over five years, dropping a percentage point each year. This puts New Hampshire on the path to becoming the ninth state to have no tax on personal income.

The budget reduces the Meals and Rooms Tax, a levy on restaurant and hotel bills, from 9% to 8.5%.

And finally, the budget incorporates the provisions of Senate Bill 3, which would shield New Hampshire businesses from tax liability on loans received through the federal Paycheck Protection Program.

Property Tax Relief

The most expansive set of tax changes occur on property taxes, which fund state, county, municipal, and school district expenditures. The final budget package includes a House provision lowering the Statewide Education Property Tax (SWEPT) by $100 million in 2023. This is a direct tax cut for every property owner in New Hampshire.

The budget also increases revenue sharing with municipalities under the Meals and Rooms Tax. While the last budget sent approximately 22% of these revenues back to cities and towns, this package sets revenue sharing at 30% and sets them aside in a newly created dedicated fund. Meals and Rooms Tax revenues have been a popular target for state budget writers in both parties over the past two decades. In total, this budget would increase M&R revenue sharing by $50.5 million to a total of $188 million.

The budget increases funding for county nursing homes by $29.1 million. It also prevents a drop in the state’s education funding formula caused by the drop in fall enrollments and the Free and Reduced Lunch program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Left unaddressed, this would have resulted in a $67 million reduction in state aid to local school districts. The budget also contains $30 million for school building aid, $35 million targeted to school districts with the greatest fiscal need, and $1.9 million for schools shifting to full-day Kindergarten.

Remarkably, the state budget would provide tax relief on all four sections of every Granite Stater’s property tax bill: state, county, municipal, and school.

School Choice

The Senate has included the provisions of SB 130, the Education Freedom Accounts Act, in HB 2. This expansion of school choice would provide New Hampshire families earning up to 300% of the federal poverty level with scholarships funded by the state’s adequate education grants. They could use these scholarships for a wide range of educational alternatives, including non-public schools, remote learning hardware and software, transportation costs, and even tuition at another public school or the New Hampshire Community College System. Our analysis projected that these accounts would save taxpayers $6.65 million in the first two years alone while improving student outcomes.

Late-Term Abortion

Currently, 43 states limit late-term abortions. The current budget package would add New Hampshire to that list, prohibiting the practice after the 24th week of pregnancy expect in cases where the procedure would protect the life, health, or well-being of the pregnant mother. The budget would also strengthen current state statutes barring the use of taxpayer funding for abortion services, requiring regular audits of abortion providers.

Critical Race Theory

Opposition to the teaching of Critical Race Theory in schools prompted responses in both the New Hampshire House and Senate. The House approach, House Bill 544, was a ban on “divisive concepts.” The Senate took a different tack, strengthening the state’s existing non-discrimination laws to prevent the the state, in training materials or in K-12 education, from asserting as fact that people of a particular age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, creed, color, marital status, familial status, mental or physical disability, religion, or national origin are inherently superior or inferior to any other. The Senate language, which also provides a legal path for those who believe they have been exposed to such discrimination, has been added to the state budget package in HB 2.

Emergency Powers

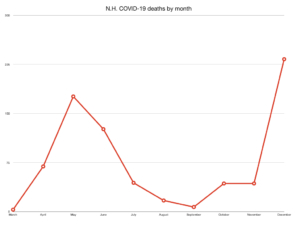

The final hurdle to a budget deal is a limit on the broad emergency powers granted by the New Hampshire Legislature to the governor following the attacks of September 11, 2001. The current emergency statute gives the House and Senate the authority to terminate any state of emergency declared by the governor by majority vote of both chambers. But it does not explicitly give the Legislature the authority to rescind individual emergency orders issued under such a state of emergency, nor does it provide a smooth path for such a resolution to come to floor of the House or Senate.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Gov. Chris Sununu issued dozens of executive orders. Some were waivers of state regulations, enabling health care workers to provide treatment free from red tape or allowing restaurants to serve beer and wine to go. Others, such as the statewide mask mandate, met with opposition from conservatives and libertarians concerned about government overreach.

Last year, with the legislative session cut short and limited to brief meeting on the UNH campus, Democratic leaders blocked attempts by a handful of legislators to address the state of emergency. This year, lawmakers dealt with a number of bills curtailing the governor’s emergency powers or codifying emergency procedures into state law, but never voted on whether to end the overall state of emergency.

The House position would have maintained gubernatorial authority to declare an emergency, but would have required a vote of the House and the Senate for it continue past 30 days. The Senate position would have clarified the Legislature’s ability to address individual executive orders and would have allowed a governor to renew any order unless and until both the House and Senate voted to cancel it. This has been a major point of contention between the two chambers.

The final compromise contains elements of both approaches. Governors in future emergencies would be able to renew any emergency order. But should any state of emergency last as long as 90 days, the governor would need to explain the continued need directly to the Legislature, which would then vote in each chamber whether to terminate the state of emergency. Should majorities of both the House and Senate approve, the state of emergency would end immediately. Much like a veto override, both chambers would need to agree to rescind the governor’s directive, though by a simple majority vote of each.

This compromise would ensure that the Legislature would have the chance to affirm or deny a governor’s emergency declarations with an up for down vote. It gives legislators a considerable amount of power while maintaining a governor’s ability to act swiftly to respond to an emergency.

In sum, this budget represents the largest bundle of conservative policy achievements passed in a single bill in living memory.