Charlie Arlinghaus

November 26, 2014

As originally published in the New Hampshire Union Leader

Tis the season for budget games. The groundwork is already being laid for tax increases and budget gimmicks all in the name of a balanced and equitable approach to government. We can only hope that the newly elected are less susceptible to these siren calls than the lot that came before them.

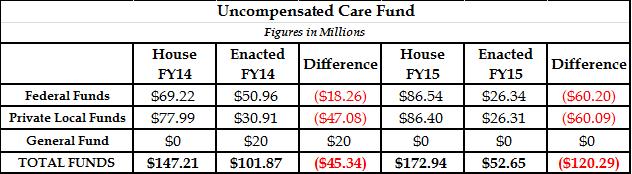

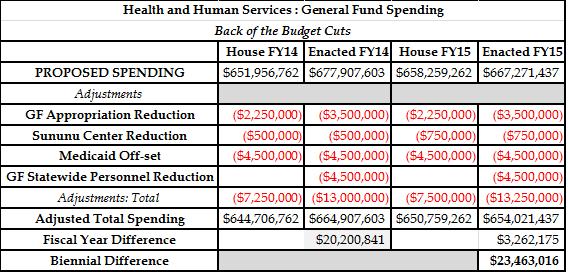

We’ve talked in the past quite often about the mess the state’s budget is in. A month before the election, the governor announced that a shortfall had developed and that she needed department heads to find $30 million in budget cuts just to balance the current two-year budget that expires in seven months. In addition to the $30 million, the department of Health and Human Services had a hole of another $45 million.

This week, with the election long in the rearview mirror, the governor came to the Legislative Fiscal Committee with a list of suggested cuts. But it isn’t anywhere near long enough to close the gap. The budget gap as described by the governor – and she has access to information the rest of us don’t and the legislature doesn’t yet – is $45 million at HHS and $30 million in the rest of government. To offset that $75 million hole, she proposed cuts of $18 million this week.

You don’t have to be a genius at the round hole and square peg game to figure out that $18 million can’t plug a $75 million hole.

So did the hole disappear suddenly or is there something else in the offing? We have a hint as to what’s coming in the governor’s speech. She talked about the problems we all know exist: the current shortfall, lawsuit settlements driving HHS spending, and a big increase in Medicaid caseloads from sources other than expansion. But she also talked – as she has repeatedly for months now – about a supposed business tax problem.

She has regularly suggested that minor changes to business taxes have given the state a big revenue problem. The implication is that the budget hole is a revenue problem. Fortunately, publicly transparent revenue numbers tell a very different story.

We often have budget problems when legislators do a poor job estimating revenues. In the current budget, the estimates were the result of the final examination in the Senate led by since retired Sen. Bob Odell – a man with a reputation among friend and foe for caution.

Odell’s estimates were adopted in the budget and have proved remarkably accurate. In year one, the budget guesstimated $2,169 million. The actual raised was $2,171 million. In the first four months of the second year, we budgeted $529 million but raised $530 million. The total variation through the first 16 months of the budget is just one-tenth of 1% — a ridiculously accurate estimate by traditional standards.

Some taxes are up more and some are down more but the hallmark of a good estimate is that the different variations among the basket of taxes will average out to make the sum more accurate. In short, there is absolutely no short term revenue problem. The budget has raised almost precisely what it was projected to and just a tiny bit more.

There are two real possibilities for the “we have a tax problem” rhetoric. The first is that the next budget will try to find tax changes here and there to “enhance revenues.” Changing thresholds, reasonable deductions, and definitions of what’s taxed are clever ways raise taxes while pretending you aren’t. Classic examples include extending the Meals and Rooms tax to rental cars which aren’t traditional meals unless you’re really hungry. The same tax was briefly extended to campsites before lawmakers recovered their sanity and repealed it. Look for deduction and filing threshold changes to be proposed in the winter.

Second, so-called revenue problem chatter is always one of the precursors to dedicated fund raids – a classic New Hampshire gimmick. Taking other people’s money from the JUA fund was the most egregious (and stopped by the courts) but “converting” fee revenue legally dedicated to a purpose and instead spending it on operations is an all too common tactic and one that lawmakers should resist.

The budget situation isn’t complicated: we raised just what we budgeted but spent a great deal more. By definition, that isn’t how budgets are supposed to work.