Joshua Elliott-Traficante

June 2015

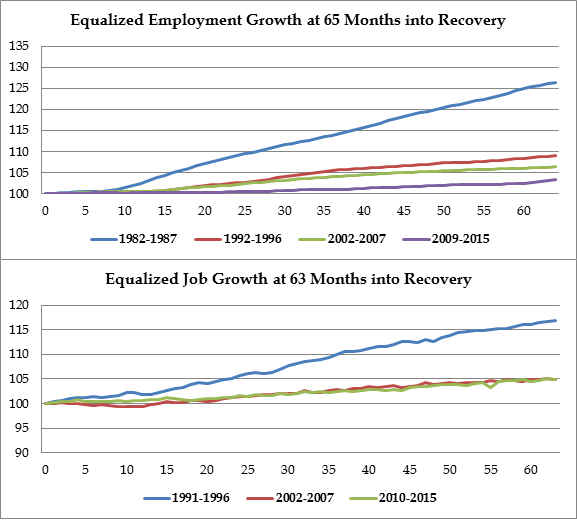

Summary: Despite a history of leading the region out of recessions, New Hampshire’s recent track record of job creation falls well short of that legacy. Only as of March 2015 has the state returned to prerecession levels of employment and jobs numbers. This paper compares the last three recoveries to the current one, detailing the state’s increasing difficulty in recovering from economic downturns.

New Hampshire has a strong track record of economic growth, especially in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s. This economic prowess helped give birth to the phrase “The New Hampshire Advantage” and made the state the envy of the region. Since 2002 however, the stiff wind that once filled the state’s economy’s sails has become a gentle zephyr at best. The last thirteen years in particular have seen mediocre growth in both employment and jobs. The recovery from the latest recession has been particularly slow. More than 5 years after the bottom of the recession, the state has only just recently returned to prerecession employment levels and jobs numbers.

Definitions and Layout:

Though ‘employment’ and ‘jobs’ are often used interchangeably, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has distinct definitions for each term, which will be used in this paper. ‘Employment’ counts the number of people employed based on where they live. ‘Jobs’ counts the number of paid positions based on where they are located. The employment figure for New Hampshire counts every state resident that has a job, regardless of where the job is located, while the jobs figure for New Hampshire counts the number of jobs based here, regardless of who fills it. For example, someone who lives in New Hampshire, but works in Massachusetts, would show up in the New Hampshire employment number, but their job would be counted in the Massachusetts job number. It is important to note that the unemployment rate is calculated off of the employment numbers, and not jobs numbers.

For this analysis, roughly the first 5 years of each of the last four recoveries are examined. The starting point is the lowest point in the recession (in terms of employment and job numbers), continues through the first 65 months of the recovery for employment numbers, and 63 months of for jobs numbers. This time frame has not been chosen arbitrarily; the state is now 65 months into recovery in terms of employment number and 63 months into recovery in terms of jobs. Doing so, accurately compares how well New Hampshire has recovered from economic downturns in the past, versus today.

Click here to read a pdf verson of the full report