Josh Elliott-Traficante

May 2015

Supporters of bringing commuter rail north from Lowell into New Hampshire have been touting the economic development potential of the project. But does rail in and of itself, construction and operation aside, create jobs? While studies of proposed passenger commuter rail lines often predict job creation, studies of lines that have been built and operating have found that these projects do not create jobs by themselves, but they can influence where already planned investments will happen.

The proposed MBTA extension would not be New Hampshire’s only passenger rail connection. The Downeaster, which runs ten trains a day between Boston and Maine, makes stops in Exeter, Durham, and Dover.

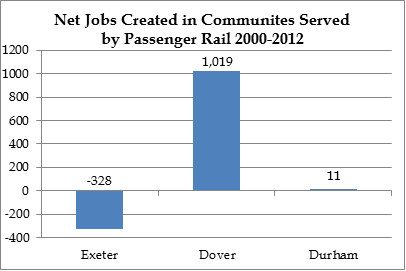

Service began in 2001, which provides an excellent case study to gauge the impact of rail here in the state. According to US Census data, after more than ten years of passenger rail service, the number of jobs increased in Dover, remained virtually unchanged in Durham, and fell in Exeter.[1]

The St. Louis Federal Reserve has some words of wisdom for those who view rail as a tool for boosting the economy: “Rather than relying solely on rail to create economic development, city planners and officials should first address a key question: Why is economic development not occurring in a given area in the first place?”[2]

The Experience Studies:

While most proposed rail projects usually include projections of job growth, it is important to remember that these are projections, not actual experience. Rather than rely on these, looking at studies of passenger commuter rail lines that have been in service for a few years is more helpful. These studies have shown that simply having rail service does not create jobs.

The most comprehensive analysis of rail’s impact on job creation was commissioned by the Federal Transit Administration and concluded that “(r)ail transit investments do not stimulate real economic growth; rather they only influence where already-committed growth takes place,”[3] adding that “rail investments cannot overcome the effects of a weak regional economy.”[4] One example the FTA study looked at was the experience of two cities along a commuter rail line in Pennsylvania. One city had substantial growth in both apartment development and commercial real estate, while another city had nearly none. They concluded that the rail line had not influenced outcomes, but the difference was a result of different attitudes towards growth, zoning laws, and land availability.[5]

More recent studies have come to similar conclusions. The experience of the Coaster commuter rail line in San Diego is particularly helpful because it shares many similarities to the proposed Capitol Corridor project. Both are roughly the same length and both connect midsized cities (40,000-100,000) to the largest city in the region. A study of the impacts of the Coaster found that though there were minor gains in value for some types of residential property near the non-Downtown San Diego stations, commercial property values fell nearly 10%.[6] Though an inexact proxy, weak demand for commercial property is not indicative of strong job growth. If the same experience is realized for the Capitol Corridor, Boston could gain jobs at Manchester and Nashua’s expense.

Researchers at the Brookings Institution also found little evidence that rail transit investments have significant impacts on urban form. The only way for rail to have an impact, they found, would be to make private car ownership and usage prohibitively expensive.[7]

Closer to home, a study of the MBTA commuter rail system, the operator proposed for New Hampshire, found that “development patterns are governed by the dominant forces of the day, and even given the large investments, commuter rail is no longer one of those forces.”[8] The director of Harvard’s Rappaport Institute, which conducted the study, summarized the findings stating “(T)he history of commuter rail in Massachusetts suggests that while commuter rail can be helpful, it generally has not revitalized communities or reduced sprawl.”[9]

The St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank conducted research into the economic impacts of light rail, and found that “the general consensus from the academic literature and the findings in this report is that light rail is not a catalyst for economic development, rather light rail can help guide economic development.”[10] In other words, rail does not create growth, but can impact where that growth happens. Though light rail and commuter rail fulfill different transit needs, the underlying argument that proponents use, that rail creates jobs, is the same.

The New Hampshire Experience: The Downeaster

New Hampshire has an excellent test case with the Downeaster, which runs from Boston north to Brunswick, Maine, and makes stops in Exeter, Durham, and Dover. Service to all of these stations began in December 2001. Though the Downeaster is technically not a commuter rail service, it is a functional equivalent by offering multiple departures a day and runs over a fairly short distance.

According to the data from the US Census Bureau, job creation between 2000 and 2012 between each of these towns is mixed. In Exeter, the total number of jobs located in the town dropped about 300. In Durham, the number of jobs was virtually unchanged, while Dover saw just over 1,000 new jobs.

These municipalities do not exist in a vacuum, so it is useful to pair them with similar, non-rail served communities, to act as control. Exeter was paired with Epping and Dover with Rochester. Durham, only seeing minor changes in jobs numbers, was left unpaired.

Epping and Exeter:

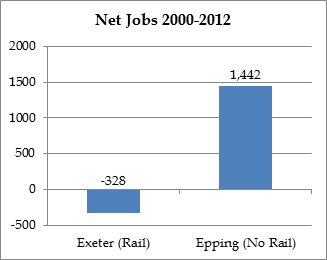

From an infrastructure point of view, Epping and Exeter are quite alike; both have access to NH 101, which links the Seacoast with Manchester. Exeter has three exits off the highway, with a fourth just over the line in Stratham. Epping has two exits off 101, with a third just over the line in Brentwood and is roughly equidistant between Interstate 95 and Interstate 93.

Demographically, Exeter is more than twice the size of Epping, although Epping added nearly four times the number of people (935) between the 2000 and 2010 census that Exeter did (298). Despite having similar highway access, and Exeter having a much larger population and a passenger rail station, Epping added 1,442 jobs over the time period, while Exeter lost 328.

Rochester and Dover:

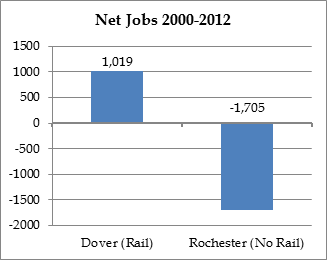

Rochester and Dover are similar communities in in terms of transportation connections. Both are close to, or on the Maine border and have four exits off of the Spaulding Turnpike, which connects to Interstate 95 in Portsmouth.

Population wise they are virtually identical; Rochester has 29,752 residents, while Dover has 29,987. In the last census, Rochester added 1,291 people, while Dover added 3,103, displacing the former as the fifth largest city in the state. Though the two cities are next to each other, the economies are quite different.

Dover’s job base is more service oriented, with a large number of jobs in insurance and finance (Liberty Mutual) and healthcare (Wentworth Douglass Hospital). The latter is particularly significant as one of the few bright spots in jobs market has been in the healthcare sector. Rochester’s economy on the other hand is more manufacturing oriented, a sector which saw 35,000 jobs lost statewide in this time period. The city was not immune to that decline, losing more than 1,700 jobs.

Drawing Conclusions:

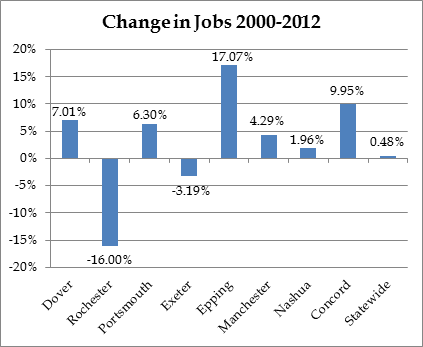

An analysis of town by town jobs numbers here in New Hampshire shows that merely having access to passenger rail does not create jobs. After a decade of continuous rail service in Dover added jobs, Durham remained unchanged, while Exeter lost jobs.

Can Dover’s impressive growth be attributed to regular passenger rail service? Not necessarily; both Epping and Concord saw greater growth rates over the time frame, and neither has passenger rail service. With the exception of the redevelopment of the downtown mills, the majority Dover’s growth has been on the peripheries of the city in industrial and business parks.

It does not appear that Rochester’s loss has been Dover’s gain either. Comparing the jobs figures, there is no evidence that Rochester’s lost jobs simply moved to Dover. Rather, larger employment trends explain this shift. Statewide, the number of manufacturing jobs has fallen by more than 35,000, replacing them with roughly the same number of service sector jobs. Dover, with its large service sector, was well positioned to benefit from this trend, while Rochester, with its large manufacturing sector, was harmed by it.

Exeter’s loss of jobs is particularly telling because it turns the entire notion that rail service creates jobs on its head. The argument that rail minimized Exeter’s job losses does not hold much weight since neighboring Epping saw substantial gains.

What does this tell us about commuter rail’s ability to create jobs? From the studies that have been conducted after rail service has started and the experience of the Downeaster here in New Hampshire, simply having commuter rail does not create jobs. Rail, whatever its benefits may or may not be, is not a tool to spur job creation.

Click here to download a PDF version of this report.

[1] United States Census Bureau, ZIP Code Business Patterns Survey

[2] Thomas A. Garrett, St. Louis Federal Reserve, “Light Rail Transit in America” pg 25.

[3] Federal Transit Administration, “An Evaluation of the Relationships Between Transit & Urban Form” Pg. 11.

[4] Ibid 15.

[5] Ibid 16.

[6] Robert Cervero and Michael Duncan, “Land Value Impacts of Rail Transit Services in San Diego County” Pg. 24.

[7] Brookings Institution, Urban and Regional Policy and Its Effects, Vol. 3. Pg 284.

[8] Eric Beaton, “Impact of Commuter Rail in Greater Boston” Pg 46.

[9] David Luberoff, “Commuter Rail Can Take Us Only So Far”, Boston Globe, November 3, 2006.

[10] Garrett, St. Louis Federal Reserve, “Light Rail Transit in America” Pg 25.