The January, 2023, draft of the state’s Capital Corridor commuter rail study contains nothing that commuter rail boosters should like. The financial analysis, prepared for the state Department of Transportation by AECOM Technical Services Inc. of Manchester, envisions a nearly $800 million railroad serving fewer than 100 Manchester commuters per trip, at an operating cost of $17 million per year. This represents a dramatic increase in costs and a devastating collapse in ridership since the DOT released its first Capital Corridor study in 2014.

The report’s own dismal numbers show that Manchester-Boston commuter rail would squander hundreds of millions of dollars to serve only a few hundred riders per day, making it a colossal boondoggle.

Failing its own goals

“The purpose of the Nashua-Manchester project (the Project) is to diversify mobility options that connect the southern New Hampshire region with the population, employment and commercial centers in the Greater Boston area, reduce congestion, emissions and travel time, and provide mobility options that promote equity and support demographic trends and preferences in the study area corridor,” the analysis states.

The report’s own numbers show that the Capital Corridor project would fail to achieve four of its five stated goals.

- The Manchester ridership projections are so low (between 38-65 riders per trip by our favorable estimates) that the line will produce no noticeable impact on congestion.

- Low ridership numbers call into question whether the rail line will produce a worthwhile reduction in emissions. And the trains will be pulled by diesel engines that will begin operation just as auto manufacturers accelerate the switch to electric vehicles, which already account for 10% of auto sales.

- The analysis projects that a trip from Manchester-Boston will take 1.5 hours by train. It currently takes one hour by car. Instead of reducing travel time, it will lengthen commute times by 50%.

- Demographic trends and commuter preferences show that Boston-area employees would rather work from home or drive a car than commute into the city via mass transit. No data supports the creation of a new rail line to feed commuters into and out of Boston.

Rising costs, falling ridership

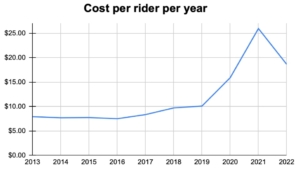

The 2023 draft financial analysis projects a total construction cost of $792 million. That is a 222.5% increase over the DOT’s original projection of $245.6 million in 2014.

Adjusted for inflation (using the national Consumer Price Index), the original $245.6 million price tag would equal $312.9 million as of January, 2023 (the date stamped on the draft study). Yet the projected $792 million cost is 150% larger than that.

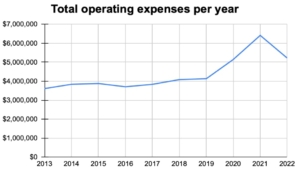

The analysis projects annual operating and maintenance costs to be $17.27 million, a 60% increase from the 2014 projection of $10.8 million. Adjusted for inflation, the 2014 price tag would come to $13.76 million. The new projection is $3.51 million, or 25.5%, higher than that.

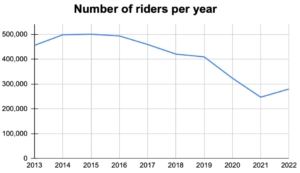

As projected costs soar, projected ridership collapses.

Both the 2014 and 2023 studies assume 16 commuter rail trips per weekday between a downtown Manchester station and Boston. The 2014 study projected a baseline average weekday ridership of 3,120 passengers on this line. That comes to 195 riders per trip.

The 2023 analysis does not project riders per weekday. Instead, it offers annual totals, which mask the collapse in projected daily ridership.

The 2023 report projects an annual Manchester-Boston ridership of 271,538. That can be divided by 52 to get 5,221 riders per week. The report assumes some ridership on weekends, at a lower rate than weekdays, but it doesn’t break down the averages by day. If we generously include all weekend riders as daily commuters (which inflates the daily commuter numbers) and simply divide the weekly ridership by five, we get a mere 1,044 riders per weekday. That’s a 66% drop from the 2014 projections.

Since 2014, the baseline assumption for ridership has fallen by 66% while the cost of building the line has increased by 222.5% and the cost of operations and maintenance has risen by 60%.

That 66% decline in ridership comes before the study attempts to account for the effects of COVID-19 and its aftermath.

The study offers a low, medium, and high COVID impact analysis. Using the same method as before to convert those numbers from annual to weekday riders, we get the following:

Low COVID impact daily ridership: 835

Medium COVID impact daily ridership: 824

High COVID impact daily ridership: 612

When COVID’s impact is factored into ridership projections, the $792 million rail line is projected to transport 612-1,044 riders per weekday between Manchester and Boston. That comes to an average of 38-65 riders per trip, at a cost of $17.27 million per year.

The analysis includes ridership projections for a Manchester-Boston Regional Airport station and a Nashua station. Those projections are higher than its projections for a downtown Manchester station. But those figures still represent significant declines in ridership from 2014 projections, with one possible exception. The projected ridership at a South Nashua Station could be slightly higher than the 2014 projections for a hypothetical “minimum commuter rail” option in Nashua, depending on how many weekend riders the new study anticipates. As mentioned above, we had to lump weekend riders into the weekday calculations since the study used only annual totals. But the bottom line remains that the study’s own projections show huge declines in ridership under most scenarios, and all Manchester scenarios, including the 2014 report’s “Manchester Commuter Rail” option that featured 20 trips per day.

Unusual revenue assumptions

In addition to astronomical costs, the 2023 draft report assumes that fares (and some advertising) will cover an astronomical share of operating and maintenance expenses.

“The primary long-term source of O&M funding is fare revenue,” the report states. “This is a relatively unusual situation,” the analysis concedes. It claims its numbers can be justified because trains will be based in Manchester, thus ending the practice of starting and ending each trip with an empty train emerging from or returning to Boston.

In the study’s “medium ridership scenario,” which serves as the basis for its revenue projections, fares cover 81.5% of operating and maintenance costs. Its low COVID impact scenario assumes that fares would cover 93.4 percent of O&M costs. Its high COVID impact scenario assumes fares would cover 58.4% of costs.

To get a sense of how realistic these figures might be, one can look at MBTA commuter rail revenues and expenses. In fiscal year 2019, the last year before the COVID pandemic, operating revenue covered 43% of MBTA commuter rail operating expenses, according to the MBTA’s audited financial report. In fiscal year 2022, revenues covered just 14% of MBTA commuter rail operating expenses, according to that year’s audited financial report.

Such large declines in fare revenues and ridership have occurred nationwide. In San Francisco, fares covered roughly 2/3 of Bay Area Rapid Transit’s operating expenses for the 2019 fiscal year. By the 2021 fiscal year, fares covered just 12% of operating expenses, The Wall Street Journal reported last week.

In January, Mass Transit Magazine reported that “commuter ridership is disappearing.”

“Transit ridership across the U.S. has been sitting steadily at about 65 percent to 70 percent of pre-pandemic ridership across transit networks, according to data from the Transit App. This is an improvement from a year ago, when ridership hovered around 55 percent of pre-pandemic ridership.

“These sorts of headwinds, driven by significant changes in the way workers and others move around urban areas, will prompt transit agencies to rethink service delivery and other aspects of their operations, say experts.”

The DOT’s 2023 financial analysis assumes that fares will cover nearly all the operating costs of the Lowell-Manchester line even as subsidies cover nearly all of the MBTA’s existing commuter rail operating costs post-COVID.

MBTA commuter rail costs rose by 5.8% from 2019-2222 while operating revenue decreased by 66%, agency audits show. This has led to a rethinking of the MBTA’s offerings.

“We’re going to have to figure out a way to operate with lower fare revenue, and it remains to be seen how much lower it’s going to be,” MBTA General Manager Steve Poftak told The Wall Street Journal last March.

The state’s projected operating subsidy totals $25.2 million during the first three years of operation, as ridership is scaled up. After that, it is projected to settle at $200,000 per year. But if fare revenue doesn’t materialize as planned, the state subsidy would remain high, potentially consuming millions of dollars per year. This backup state subsidy ultimately makes state taxpayers the default financier of the rail line’s ongoing operations. If ticket revenues don’t materialize, the state would be stuck either covering those losses or ending service.

Local station costs

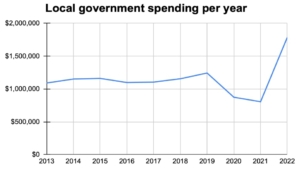

“The financial analysis assumes that the cities of Manchester and Nashua fund the construction, O&M, and renewal costs of their respective downtown stations,” the report states.

It anticipates construction of a Manchester station at an estimated $51 million, including financing costs, and a Nashua station at an estimated $31 million, including financing costs.

It assumes that Manchester will use meals & rooms tax revenue and Nashua will use local property tax revenue to pay for most of the construction. If taxpayers and elected officials refuse, then what?

The report states that the Manchester-Boston Regional Airport would pay to build the proposed airport station. It does not explain how Nashua’s second station would be funded.

Population density

Any study of commuter rail viability should start with population density. It’s considered a rule of thumb that a city needs a core population density near 10,000 people per square mile to make commuter rail successful. Yet nowhere does the financial analysis mention population density, on which a rail system’s financial viability depends.

That’s a serious omission. As we’ve noted before, Boston has a population density of 13,967.7 people per square mile, and Lowell ’s density is 8,489.8 per square mile. Manchester’s density is just 3,496 people per square mile. It doesn’t have a single zip code with a density of even 4,000 per square mile. Nashua’s density is just 2,961.7 per square mile.

U.S. Census data put Manchester’s population density at 3,310 per square mile in 2010. In the decade from 2010-2020, the city’s density grew by just 186 people per square mile. At that rate, Manchester will reach 10,000 people per square mile in 350 years. If the city’s growth rate somehow doubled, it would still take 125 years to get to 10,000 people per square mile.

The report makes no effort to explain how a commuter rail line could be viable over the long term while serving such low-density cities as Nashua and Manchester.

Shifting work-life patterns

In addition to the density issue, there are numerous questions regarding the suitability of building a commuter rail line from a sparsely populated state into a shrinking city at a time when technology is changing the way we work.

Suffolk County, Mass., which includes Boston, lost 28,000 people from 2020-2022, Census data show. Boston commercial vacancies early this year hit their highest rates in a decade, as demand for office space fell.

Several studies of Boston and Massachusetts commuters and employers (see here and here) have found significant declines in both mass transit use and the desire to commute via mass transit to offices in Boston.

Most people want to work from home at least part of the week. People are fleeing many large cities, including Boston, in search of a more suburban lifestyle. Transit agencies around the country are factoring these shifting preference into their future plans. If these shifts represent a permanent change in American work and commuting patterns, as polls and changing behaviors suggest, now would be a particularly bad time to build a new point-to-point commuter rail line.

Opportunity costs

The 2023 study proposes that the state would cover between $147.6 million and $185.4 million of the anticipated construction costs. If spent on commuter rail, that money could not be used for other state transportation priorities, of which there is no shortage.

For comparison, Exit 4a in Londonderry is projected to cost $61.6 million to build, and the benefits are concentrated entirely in New Hampshire. This exit on I-93 is expected to boost economic development in Derry and Londonderry, reduce congestion and improve safety on local roads. The state could finance almost three projects of this scale for the high-end cost of the Capital Corridor rail line. And the benefits would be spread among a large share of New Hampshire’s population, rather than split among employers in Manchester, Nashua and Boston.

The state’s current 10-year Transportation Plan dedicates $151.49 million to bridges this year. Bridge repair costs over the next decade exceed $900 million. When that level of need exists, it’s hard to justify spending more than a year’s worth of bridge repairs on a new rail line that would serve few people.

If the state were to create a list of the best possible ways to spend $185 million in transportation dollars, a rail line for the dwindling percentage of people who want to commute daily between Manchester and Boston would not make the top ten. The state has much higher transportation priorities.

Conclusion

The DOT’s own analysis shows that there is no scenario in which building a $792 million commuter rail line in the near future makes financial sense for New Hampshire. Construction and operating costs are rising much faster than inflation, while projected ridership is collapsing. Commuter rail does not extend from Lowell, Mass., into New Hampshire for good reason. It’s too costly and would serve too few people. This draft study confirms that.

Download a pdf copy of this policy brief; DOT Capital Corridor 2023 Brief

Editor’s note: Some of the percentage increase figures in the initial post contained typos. They have been fixed.