Executive summary: Funding for the state’s Division of Children, Youth and Families has become a contested political issue in this year’s state elections. Framing the debate, former state Sen. Molly Kelly, the Democratic nominee for governor, asserts that the 2018-19 state budget signed by Gov. Chris Sununu prioritized tax cuts for the wealthiest corporations over child protection, thereby draining state revenue and leaving the division with less funding. This briefing paper takes a look at those claims.

We find that the 2018-19 state budget signed by Gov. Sununu provided DCYF with its largest general fund spending increase in at least a decade. We find as well that the business tax cuts included in the budget were not targeted to the wealthiest corporations and did not cause DCYF funding reductions.

DCYF Funding

NOTE: Until the 2014-15 state budget, the Division of Children, Youth and Families was a separate division of the Department of Health and Human Services, listed as a single category in the state budget. Starting in that biennium, DCYF was no longer listed in the state budget as a division. Its funding was divided into DCYF’s two primary component parts, “Child Protection” and “Child Development.” To make sure we were comparing apples to apples over the past decade, we asked the Legislative Budget Assistant to verify what budget categories constituted DCYF funding during that time period. The spreadsheet accompanying this brief (attached at the bottom of this post) is the LBA’s breakdown of DCYF’s core Child Protection and Child Development funding over the past decade, with the Sununu Youth Services Center budget shown separately.

As with other state agencies, state general fund appropriations for the Division of Children, Youth and Families have fluctuated with the state’s financial fortunes. In the last decade, both political parties have cut state general fund spending on DCYF in leaner times and increased it when more money was available.

For example, the 2010-2011 budget was signed by Democratic Gov. John Lynch and written by a Democratic legislature, with Democratic Sen. and future Gov. Maggie Hassan taking the lead in the Senate. It cut state funding for Child Protection by 12 percent from 2009-2010 and for Child Development by less than a percentage point.

The Republican-led Legislature cut state DCYF funding further as part of its broad spending reductions in the 2012-13 budget, which Gov. Lynch let pass without his signature. In the 2014-15 and 2016-17 budgets, DCYF state funding inched slightly higher.

Then in the 2018-19 budget, Gov. Sununu and the Republican Legislature substantially increased state funding for DCYF. State general fund spending on Child Protection rose from $39,855,790 in 2017 to $45,857,006 in 2018, then to $47,688,777 in 2019. State General Fund spending on Child Development rose from $10,886,714 in 2017 to $11,391,914 in 2018 to $11,849,106 million in 2019.

In total, state General Fund spending on DCYF was increased in the 2018-19 budget by $8,795,379, or 17.3 percent.

No other budget in the last decade comes close to increasing DCYF funding by as large a percentage as the budget Gov. Sununu signed in 2017. Far from neglecting or underfunding DCYF, the 2018-19 budget treated it like a favored child.

Business Tax Cuts

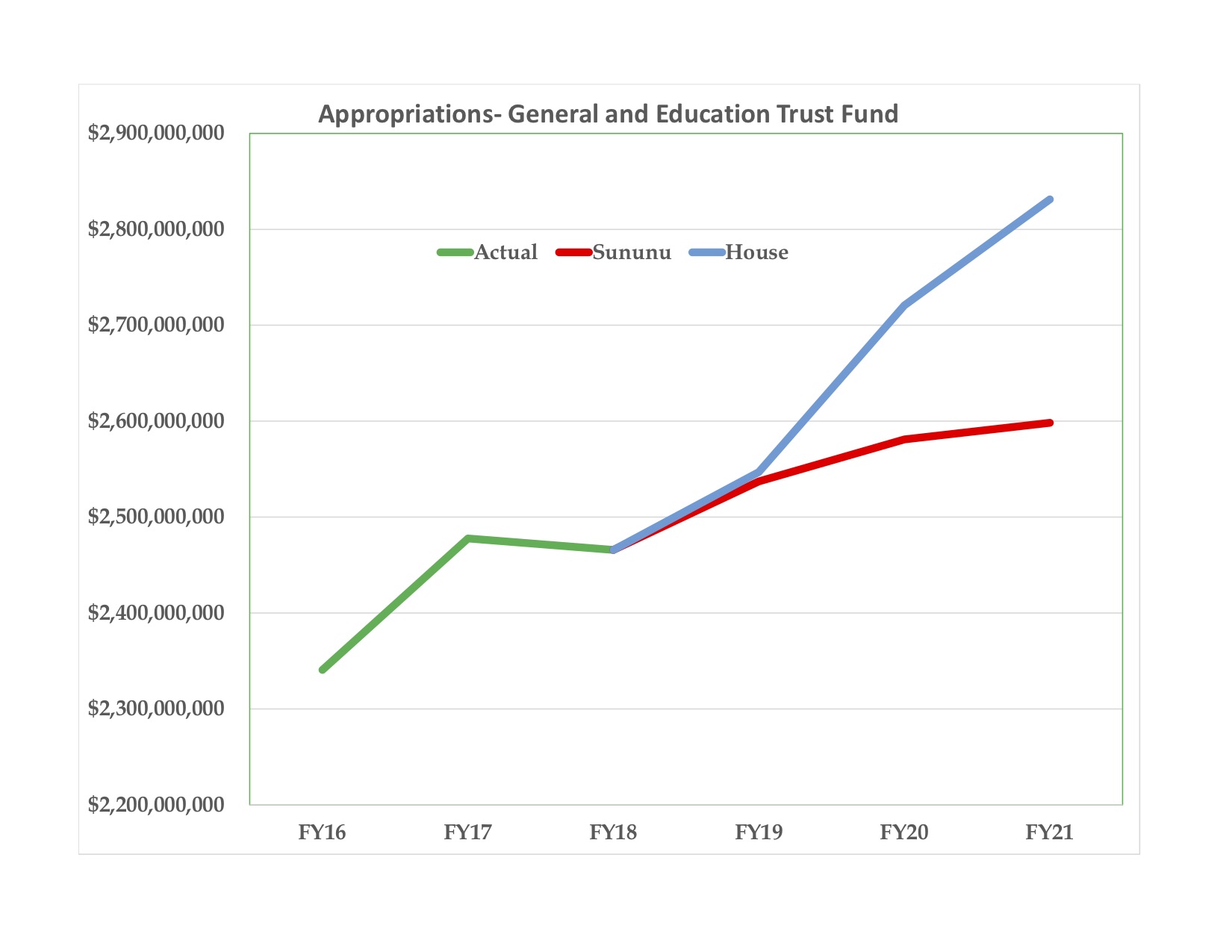

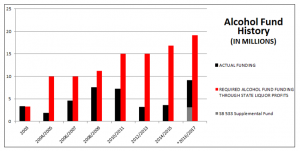

Legislators in 2015 passed business tax cuts to take effect on Jan. 1, 2016. They dropped the business profits tax rate from 8.5 percent to 8.2 percent and the business enterprise tax rate from 0.75 percent to 0.72 percent. A provision in the budget provided that the rates would fall again for fiscal year 2018 if general and education fund revenues hit at least $4.64 billion by the end of fiscal year 2017. Revenues hit $4.865 billion, easily exceeding the target, and on Jan. 1, 2018 the business profits tax fell to 7.9 percent and the business enterprise tax to 0.675 percent.

The 2018-19 budget signed by Gov. Sununu introduced another round of business tax rate reductions. The business profits tax is scheduled to drop to 7.7 percent on Jan. 1, 2019 and 7.5 percent on Jan. 1, 2021. The business enterprise tax is scheduled to drop to 0.6 percent on Jan. 1, 2019 and 0.5 percent on Jan. 1, 2021.

Opponents of these business tax cuts have for more than a year floated a talking point which asserts that the 2018-19 budget contained $100 million in tax breaks reserved exclusively for the state’s wealthiest businesses. In some cases opponents have asserted that the tax cuts were for the richest 3 percent of businesses.

Former Sen. Kelly has combined this attack with her claim that the budget shortchanged DCYF. For example, in an Aug. 30 opinion column for the New Hampshire Union Leader, she wrote:

“Sununu became governor knowing that DCYF and the state’s obligation for the safety of our children was in jeopardy. He has not done enough to fix it. Instead, his priority in his 2017 budget was giving away $100 million in tax breaks to the wealthiest corporations, when he should have ensured DCYF had every resource needed to protect our children.”

As detailed above, the budget Gov. Sununu signed in 2017 increased DCYF funding dramatically. Did it give away $100 million to the wealthiest corporations?

Neither the governor’s proposed budget nor the final state budget projected business tax revenue reductions. On the contrary, both counted on a growing economy to increase business tax revenue, which is exactly what has happened so far.

The governor’s proposed budget counted on business tax revenue growing by $31.7 million over the biennium (it also increased DCYF funding by $7.6 million). Rather than cut DCYF funding to account for lost business tax revenue, it proposed using increased business tax revenue to increase DCYF funding. The final state budget did the same thing.

The Committee of Conference that agreed on the final state budget projected business tax revenue of $662 million in 2018 and $672 million in 2019. Available data suggest that these were conservative projections. Business tax revenues for fiscal year 2018 were $776.6 million, according to unaudited state figures. That’s 17.3 percent above plan and 22.4 percent above the prior year.

How can one claim that the budget lost $100 million because of business tax cuts when it increased business tax revenue by $114 million — more than the supposed revenue loss — in only its first year?

The $100 million figure likely comes from revenue projections presented by the Legislative Budget Assistant’s Office during the budget negotiations.

The Legislative Budget Assistant provided an estimate of the cumulative value of the 2018-19 budget’s business tax cuts, which projected a revenue loss of $96 million through 2021 with another $86 million in 2022. It further estimated a $9.7 million annual loss from the budget’s expansion of allowable business profits tax deductions from $100.000 to $500,000.

There are multiple problems with using those projections as the basis for claiming that the budget took money from DCYF to give to rich corporations.

First, those estimates apply to tax law changes that take effect in 2019. If those rate reductions do materialize, they would have no effect on DCYF funding for the 2018-19 budget, which is already set.

Moreover, this theoretical future revenue loss is inconsistent with the results of the preceding business tax rate reductions.

Business tax revenue exceeded projections by $132.8 million (23.4 percent) in fiscal year 2016 and by $72.7 million (12.9 percent) in fiscal year 2017, as recorded in the state’s official Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports for 2016 and 2017. Unaudited figures for fiscal year 2018 show business tax revenues coming in $114 million (17.3 percent) above state budget projections and 142.3 million (22.4 percent) above fiscal year 2017.

Since fiscal year 2016, when the business tax rate reductions took effect, revenues from state business taxes have risen, exceeding state projections by $319.5 million.

The state has three years of data to show that business tax rate cuts did not starve the state of funding, but instead likely contributed to the increased economic activity that fueled an unexpected $319.5 million business tax windfall.

The revenue loss projections were made using static scoring, which does not take economic growth or changed business behavior into account. They represent a simple mathematical calculation of state tax receipts assuming that lower tax rates have no effect on anyone’s behavior. The state’s experience since 2016 shows why this is a bad way to project tax revenue.

Moreover, neither the projections nor the rate cuts themselves support the claim that the budget’s business tax cuts were targeted to the wealthiest corporations. The rate cuts are not targeted to wealthy corporations but apply to all businesses that have to file New Hampshire business taxes.

Conclusion

There is no factual basis for the claim that DCYF funding in the 2018-19 state budget was neglected or diminished because of reduced business tax collections. Because business tax revenue has been significantly higher than projected since rate cuts began in 2016, legislators were able to increase DCYF funding by 17.3 percent in the 2018-19 budget. The first year of that budget brought in an additional $114 million in unanticipated business tax revenue, more than making up for the alleged $100 million in hypothetical future business tax losses. Those hypothetical future losses have not caused reduced DCYF funding and are inconsistent with the results of business tax rate cuts from 2016-2018.

SYSC-DCYF Budgets

Download a pdf copy of this brief here: JBC DCYF Biz Tax Brief