“Price gouging” and the toilet paper shortage

If you haven’t stocked up on toilet paper, hand sanitizer, disinfectant wipes or milk yet, good luck. By the time you read this, your local supermarket might well be out. At noon on Friday, the Bedford Market Basket had some scattered half gallons and a single gallon-jug of milk left. (It was chocolate, indicating poor judgment on someone’s part.)

Supermarket shelves are empty all over New Hampshire as Granite Staters raid stores for milk and various sanitizing products. It’s as if the state’s been sacked by obsessive-compulsive pirates with rickets.

But it wasn’t pirates (alas). Shelves are empty because basic market price mechanisms did not kick in.

When demand surges as it did this past week, price increases typically follow. Higher prices discourage hoarding and encourage suppliers to boost production. But supermarket executives know that if they discourage hoarding by raising prices, people will accuse them of “price gouging.” So they don’t raise prices. Predictably, shortages result.

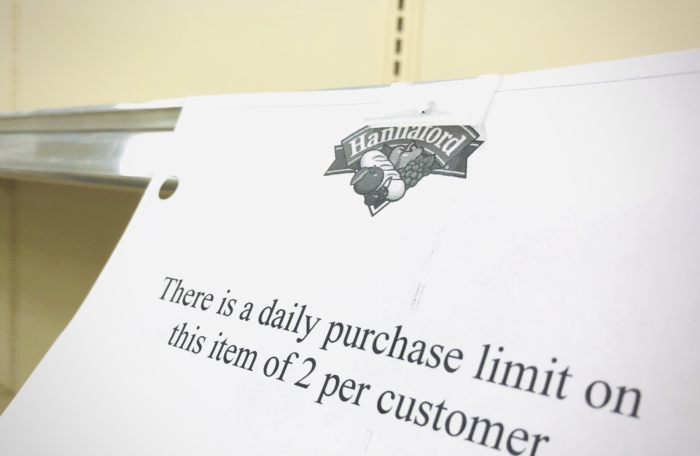

A Union Leader story that credited the shortage to “panic buying” featured a Hannaford sign taped to a bare shelf. The store “may have frequent out of stocks on many toilet paper products for the foreseeable future,” it warned.

Well, of course. When toilet paper costs exactly the same during a period of peak demand that it did the week before, buying more than you need comes with zero additional cost. You might as well buy a bunch now “just in case” because it’s the same price now as it was last week and it will be next month.

A price increase would make some people think twice about buying more than they think they’ll need. That would leave more for people who have a greater immediate need.

Unwilling to raise prices, stores have tried to discourage hoarding by imposing purchase limits. “There is a daily purchase limit on this item of 2 per customer,” read one sign at a local Hannaford on Friday. It sat on an empty shelf. Such limits are a form of rationing. They’re just not as good a form as price adjustments are.

Shortages, by the way, are also a form of rationing. They’re just a really bad one.

“Price gouging” can have different meanings. Raising the price when one has a monopoly on a good or service is one. Raising prices in a competitive market when demand surges is another. The second meaning is the misleading one. People equate the two, but they aren’t the same.

Studies done on gas price increases after hurricanes Katrina and Rita found that the prices were regular supply and demand fluctuations, not arbitrary impositions, as in the case of the monopolist. A 2007 price gouging study published in the Journal of Competition Law and Economics analyzed the impact on the economy if price gouging laws had been in effect after those two hurricanes. The authors estimated that “economic damages would have been increased by $1.5–2.9 billion during the two-month period of price increases.”

That’s because laws that ban “price gouging” are really just price caps. And price caps create shortages during periods when the market price otherwise would rise above the cap.

Economist Milton Friedman made exactly this point when writing about the U.S. gas shortages in 1973.

This week’s supermarket sell-outs are caused by the failure of prices to find their natural market equilibrium. If government forbade sellers from raising prices, the result would be the same.

Thankfully, New Hampshire has no anti-price-gouging law to make shortages even worse.

John Stossel has written about this a number of times. One aspect is that it often helps the supply side of the equation. Say I rent a truck and buy up all the toilet paper. I then sell it at marked up prices but I take it back to my neighborhood and give them the first crack at purchase. I’ve brought the supply to the demand so I should get extra on the price (everyone pays Amazon for delivery, so why not me?). Now I could be a jerk and try and charge 10x the price. I may get some sold but I’d generate a lot of ill will towards me. It’s leads back around to “exactly what is price gouging”? 2x, 5x, 30x? At some point it’s too high and demand drops off as people modify their behavior (gasoline prices are an example).