Two weeks after a supporter of the Green New Deal won the New Hampshire primary, a new study finds that paying for only a few of the Green New Deal’s largest mandates would cost the median New Hampshire household more than its entire annual income in the first year of implementation.

“The Green New Deal is a politically motivated policy that will saddle households with exorbitant costs and wreck our economy, said Kent Lassman, president of the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI) and co-author of the study. “Our analysis shows that, if implemented, the Green New Deal would cost New Hampshire households more than $74,000 in just the first year alone. Perhaps that’s why exactly zero Senate Democrats, including Senators Jeanne Shaheen and Maggie Hassan, voted for the Green New Deal when they had the chance.”

The study, by CEI and Power the Future, analyzed the cost of just a portion of the Green New Deal’s energy mandates. It estimated New Hampshire’s costs at $74,723 per household in the first year. That’s slightly ($666) higher than New Hampshire’s median household income.

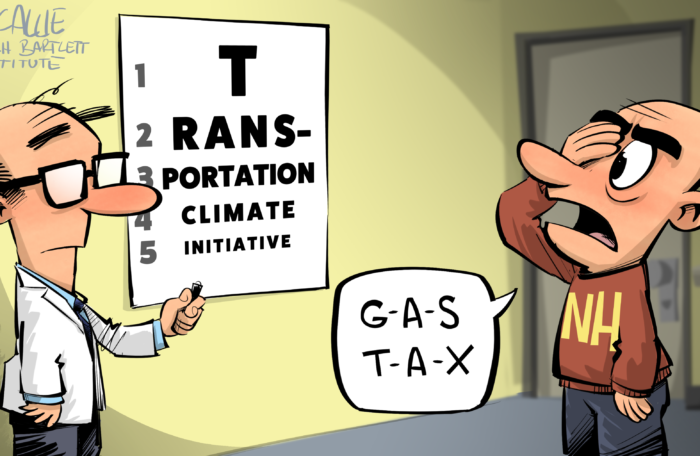

The Green New Deal sets extraordinarily ambitious goals for combatting climate change. It would mandate that all power come from zero-emission energy sources, the electric grid be converted to a “smart grid,” every building in the United States be retrofitted “to achieve maximal energy efficiency,” the government “eliminate pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector as much as is technologically feasible,” the government remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere through “low-tech” solutions (planting trees, potentially), and the government eliminate greenhouse gases from the agricultural sector as much as is technologically possible.

Those are just the environmental goals. The legislation also guarantees, among many other things, a job with high pay and paid family leave, strengthened labor laws, a halt to “the transfer of jobs and pollution overseas” and high-quality health care, affordable housing, economic security and affordable food for every American.

The study leaves out all of the non-environmental goals and examines only a portion of the environmental mandates. It estimates costs for converting residential housing to Green New Deal efficiency standards (leaving out all commercial and industrial buildings, which are covered in the law), replacing non-compliant household vehicles with electric vehicles, making ground shipping compliant with the Green New Deal, and switching to green power.

This extremely conservative estimate that excludes most Green New Deal mandates comes up with a per-household cost for New Hampshire of $74,723 in the first year, $47,310 in years 2-5, and $39,821 per year after year five.

After reaching these figures, the authors conclude that “the Green New Deal is an unserious proposal that is at best negligent in its anticipation of transition costs and at worst a politically motivated policy whose creativity is outweighed by its enormous potential for economic destruction.”

You can read the study here.