By Jason Sorens

Gov. Chris Sununu and his opponent, Sen. Tom Sherman, have proposed reforms to alleviate New Hampshire’s severe housing shortage. How do those proposals compare, and how effective would they be? A brief overview of each suggests that neither would solve New Hampshire’s housing shortage, but Gov. Sununu’s initiative would be likely to result in more housing construction.

Democratic Sen. Sherman released his housing plan for New Hampshire in July, calling it a longer-term fix than incumbent Republican Gov. Chris Sununu’s “federal band-aid,” the InvestNH Housing Fund approved in May. Of course, InvestNH is not the sum of Gov. Sununu’s housing policy, nor has he yet released a detailed plan for the coming term. Therefore, a direct comparison of the two candidates’ housing policies is imperfect at this time, but we can still assess what is good, bad, and mediocre in each set of proposals: Sherman’s housing plan and Sununu’s InvestNH Housing Fund.

Gov. Sununu’s InvestNH plan

The governor’s InvestNH program consists of $60 million in grants for owners and developers, and $40 million in grants for municipalities. In an ideal world, taxpayer dollars wouldn’t be used to subsidize a private industry at all. Yet government has created housing scarcity by strictly regulating home-building, not in the interest of health or safety, but simply with the explicit goal of preventing new people from living in the area. The obvious solution is to remove the unnecessary regulations that limit residential construction. But those regulations rest at the local level, and legislators have proven reluctant to overrule them with state laws. Using financial resources as incentives to work around or relax local regulations is a compromise that attempts to produce quick results while accepting the political reality that no statewide fix is achievable this year.

Still, if the state is going to subsidize home-building, it had better be done in efficient and effective ways. Grants to municipalities to encourage them to lift regulatory restrictions on new homes might be the most easily justified way of deploying financial resources because they attack the problem at the source: the tangle of local regulations that prevent building.

The InvestNH municipal grants consist of three streams: $30 million in grants to municipal governments on a per-building permit basis, $5 million in grants to assist with regulatory evaluation and redesign, and $5 million to cover the costs of demolition of vacant or dilapidated buildings.

Towns will get $10,000 for every building permit they issue within six months of application for new rental units constructed in projects made up of five or more units. Because of the short timeline, this money is not going to incentivize changes to zoning ordinances. Projects of this size almost always require a variance from the local board of adjustment, so this money mainly works as an incentive for those boards to approve more projects, or at least cooperate to speed them along.

The $5 million will go to municipalities for consulting on their housing needs, reviewing current regulations, and rewriting regulations. The primary goal of requests must be to increase housing stock.

The $60 million for capital grants goes directly to developers and the nonprofit New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority. Only multifamily rental housing is eligible. For projects with 15 or more units, applicants must demonstrate an “affordability commitment,” holding rents below market for lower-income tenants for at least 20% of units.

The main advantage of Sununu’s plan is that the money should indeed incentivize new housing construction in a relatively short time frame. By tying the municipal grant money to the issuance of building permits, Sununu’s plan creates a strong incentive for boards to issue more building permits. The state would, in effect, pay municipalities to issue new building permits.

The bulk of the Sununu plan, $60 million for capital grants to stimulate the construction of multifamily housing, might incentivize developers to go forward with projects that contain a higher percentage of lower-priced units than would have been profitable without the grants. Ordinances that require projects to set aside a certain percentage of units for rent at below-market rates tend to discourage development and lead to less new construction. But this cash incentive might do the opposite. It will be difficult to know, however, whether these projects would have been built anyway.

Paying municipalities to consult on housing needs and review regulations might produce better land use regulations, but that outcome is not guaranteed, and this portion of the plan lacks a strong incentive to achieve the desired result.

The strength of Sununu’s plan – that it is focused on stimulating development in the short term – is also a drawback. It does very little to change the long-term dynamics of repressed supply. It also focuses solely on larger multifamily rental projects, as opposed to single-family starter homes and “missing middle” construction.

Sen. Sherman’s plan

Sen. Sherman’s plan is less detailed, but it has these features:

- It adds staff to regional planning commissions and the state’s Office of Planning and Development;

- It funds municipal review of local land-use ordinances;

- It reviews state-level regulatory hurdles to development;

- It assesses under-used state lands for development potential;

- It promotes model zoning ordinance elements;

- It subsidizes loans for water, sewer, and transit infrastructure;

- It creates an incentive program for municipalities to adopt more pro-housing ordinances;

- It increases community development tax credits;

- It increases the affordable housing fund;

- It creates a historic rehabilitation tax credit;

- It doubles funding for contractor job training.

Sherman touts the fact that his plan features permanent programs rather than a one-time infusion of money. This might not be quite fair to Sununu, since the InvestNH program came out of a unique opportunity to spend federal grants, and the governor has strongly supported legislation that offered some structural changes, including a “housing champion program” that would reward municipalities for changing their ordinances to allow more housing density. Still, Sherman’s plan is intended to be a comprehensive menu of permanent policy changes. The question is whether they would achieve the intended goal of stimulating the construction of more housing.

Some of Sherman’s ideas can be expected to have a greater impact than others. The strongest part of Sherman’s plan is the proposal to tie increases in state transportation and environmental funding to “the adoption of zoning or infrastructure that allows reasonable opportunities for housing.”

Gov. Sununu supported a similar housing champion program that was initially included in Senate Bill 400 this year, but that part of the bill did not pass. Depending on how such a program is designed, it could have considerable long-term impact. A well-designed program will reward municipalities for actual housing unit creation as well as regulatory changes, and will reward regulatory changes that allow for single-family and “missing middle” in addition to statute-defined “workforce housing” (buildings of five units or more).

Expanding sewer access helps the environment and allows more housing and commercial density. It’s unclear how important an obstacle it is to new construction, but it could be a factor.

Sen. Sherman’s proposal for a state job training fund for the construction trades is not likely to relieve the shortage of skilled construction labor, as the funds will surely be a drop in the bucket compared to what the private sector already spends on training, and training is rarely the decisive hurdle discouraging someone from entering a manual-labor occupation.

The CDFA tax credit, which Sen. Sherman would expand, is widely alleged to favor politically connected businesses and nonprofits and doesn’t focus on housing.

The rest of Sen. Sherman’s plan would do little to stimulate new housing development. The bulk of the senator’s plan would fund studies and reviews, or give municipalities and planning commissions additional financial resources that are not tied to the issuance of new building permits or the passage of new, housing-friendly ordinances.

Whereas most of Gov. Sununu’s plan is focused on directly financing new housing construction, most of Sen. Sherman’s plan is focused on providing additional financial resources to local governments, planning commissions, and construction industry labor.

Overall, Gov. Sununu’s plan contains stronger immediate incentives for developers to propose multi-family housing, and for municipalities to issue new permits. Sen. Sherman’s plan also contains some of these incentives, but until funding details are available, it’s impossible to know how much of an impact they will have. Setting up a permanent housing champion program, as both candidates appear to support, would have the potential to change the game.

It’s worth noting that neither candidate is talking about state preemption of local regulation. Zoning preemption bills are becoming more common, and are generating more attention, in the Legislature. One nearly passed the House this year (House Bill 1177, sponsored by Rep. Ivy Vann, to legalize fourplexes wherever water and sewer are available), and several others were proposed.

With both candidates for governor backing programs to incentivize local governments to allow more housing, look for similar proposals to be introduced in the Legislature next year. But if those incentives fail to produce meaningful changes in local regulations, and the state’s severe housing shortage continues to frustrate voters, the pressure for direct preemption of local regulatory barriers will continue to build.

Dr. Jason Sorens is director of the Center for Ethics in Society at St. Anselm College.

Download a pdf copy of this analysis: Gubernatorial Candidates Housing Plans

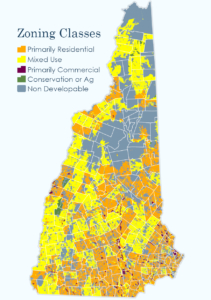

The New Hampshire Zoning Atlas is the most powerful tool Granite Staters have ever had for understanding local zoning ordinances. It catalogues—and maps—23,000 pages of zoning regulations in 2,139 districts in 269 jurisdictions. Never has this information been available in one place, much less open for public examination.

The New Hampshire Zoning Atlas is the most powerful tool Granite Staters have ever had for understanding local zoning ordinances. It catalogues—and maps—23,000 pages of zoning regulations in 2,139 districts in 269 jurisdictions. Never has this information been available in one place, much less open for public examination.