Jason Sorens at the American Institute for Economic Research has posted a provocative essay connecting young people’s affinity for heavy-handed government economic intervention to overly restrictive land use regulations.

Restrictive land use regulations play a significant role in driving housing costs higher. That’s very well documented.

Government zoning regulations that limit homebuilding are a big factor in housing costs over the long run. A lot of research has shown this, but so does common sense. Look at the populations of Boston, Houston, Miami, and San Francisco over time. Between 2010 and 2020, Boston’s county (Suffolk) grew 2 percent, Houston’s county (Harris) grew 16 percent, Miami-Dade grew 7 percent, and San Francisco County grew 8 percent. Clearly, San Francisco’s huge expense is not solely a result of hot demand; otherwise, its population growth rates would be much higher than those of the others. Boston also looks pretty bad when you compare rents to population growth, while Houston looks amazing. It has accommodated rapid growth at moderate rents.

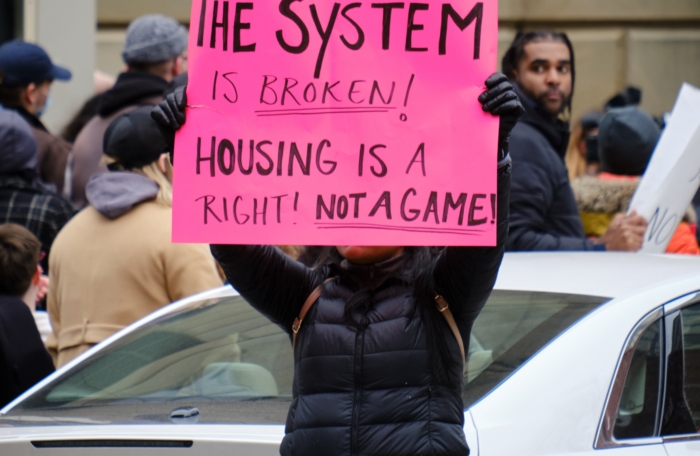

What’s less well known is that persistently high housing costs, caused by a long-term supply shortage, price younger adults out of the housing market, and in their frustration they demand government remedies. The longer the shortage persists, the more extreme their proposed remedies become.

Right now, left-of-center states and localities are experimenting with rent control and public housing, would-be solutions to the problem of rising rents that economists know are incredibly costly. Simply reforming zoning would be a better solution.

Not only do artificial restrictions on the housing supply turn people toward radical economic interventions, but they also tend to make communities more left-leaning over time.

A standard-deviation increase in housing regulation makes a place shift toward the Democrats about three percentage points over the next eight years, because noncollege voters, who are becoming the Republican base, move out.

“But won’t building apartment high-rises bring in more Democrats than Republicans?” I often hear. Yes, usually, but by increasing housing supply these high rises will make single-family homes cheaper in the suburbs, keeping blue-collar families from moving to Texas or Florida. And building tract subdivisions in the suburbs directly helps blue-collar families stay put.

Many Democrats and progressives are at least somewhat free-market on housing, because they want to keep rents down. That’s admirable. On the other hand, democratic socialist types insist on harmful “solutions” like rent control and public housing. Republicans and conservatives have largely sat on the sidelines of zoning reform so far. But the data strongly suggest that to fight the radical left, we need to build more homes.

A lot of Republicans and conservatives believe that strict zoning is a way to protect their communities politically right-of-center. The opposite tends to be true. It makes them more left-of-center over time and causes people, particularly the young, to seek more government economic interventions.

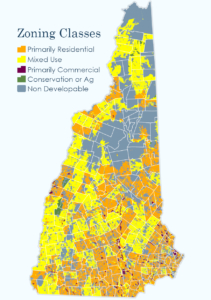

The New Hampshire Zoning Atlas is the most powerful tool Granite Staters have ever had for understanding local zoning ordinances. It catalogues—and maps—23,000 pages of zoning regulations in 2,139 districts in 269 jurisdictions. Never has this information been available in one place, much less open for public examination.

The New Hampshire Zoning Atlas is the most powerful tool Granite Staters have ever had for understanding local zoning ordinances. It catalogues—and maps—23,000 pages of zoning regulations in 2,139 districts in 269 jurisdictions. Never has this information been available in one place, much less open for public examination.